No, Britain doesn’t have first dibs on Greenland

I’ve found archive documents which show, contrary to recent reports, that Denmark icily rejected the UK’s demand to have right of first refusal if Greenland was ever to be sold

In the past couple of weeks some news reports have suggested a peculiar difficulty with President Trump’s self-proclaimed intention to acquire Greenland from Denmark – an agreement from a hundred years ago which apparently gives Britain ‘first dibs’.

Supposedly the UK has the right of first refusal if the Danes ever decide to sell the icy but strategically located and mineral rich island territory (which of course they insist they won’t). The articles, which have appeared internationally, all seem to be based on statements made by a former Danish government representative to Greenland.

In fact, I’ve located the relevant documents in files at the UK National Archives and can report that it’s not true.

The reality revealed by these papers is that in 1920 the British government did indeed tell the Danish government that they would only recognise full Danish sovereignty over Greenland in return for the right of first refusal if the island was ever sold.

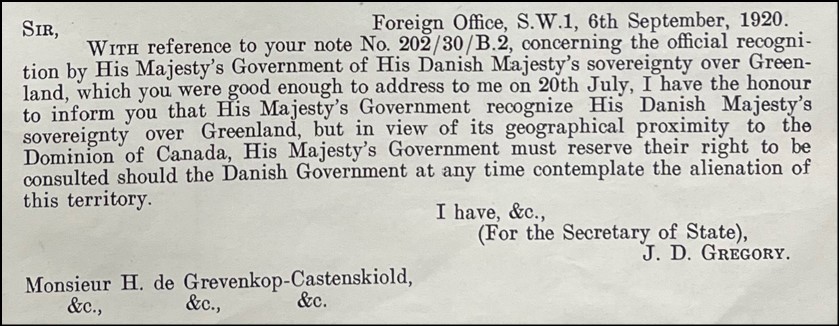

But the Danes completely dismissed this suggestion. Britain then backed down and agreed recognition, while merely asserting that if ownership was transferred then the British government ‘must reserve their right to be consulted’. To which the Danes sent no response.

Intriguingly, I also discovered that I’m not the only person who’s just been to the National Archives in Kew to search through obscure binders from a century ago containing paperwork about cryolite mining, musk oxen, trading outposts, and other aspects of life in Greenland, along with diplomatic dealings.

My access to several folders I had ordered in advance was postponed for several hours because, according to archive staff, they had been taken to be read by someone ‘from the government’.

So what do the documents disclose?

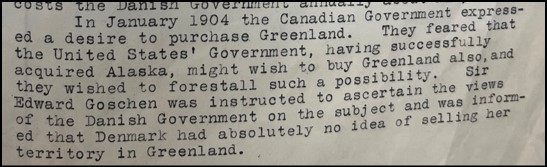

In an era when it wasn’t uncommon for colonial nations to trade land (and control over its population) for money, a Foreign Office memo shows the issue had previously arisen.

By the time of the First World War, the Danish government was extremely keen to obtain formal international recognition for its authority over all of Greenland.

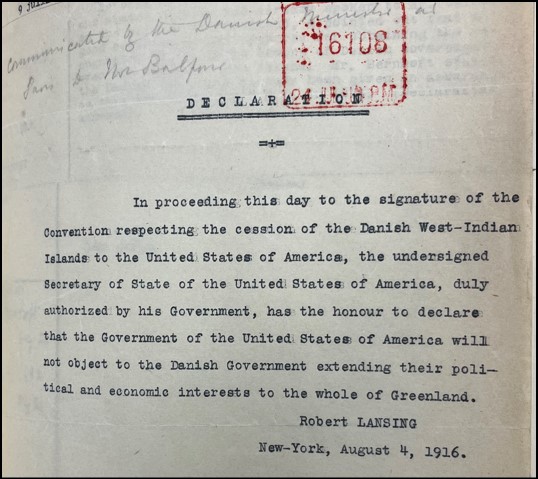

In 1916 the Danes got the United States to accept this, with the Americans thereby renouncing any claims of their own, as part of a treaty in which the US purchased from Denmark what then became called the US Virgin Islands.

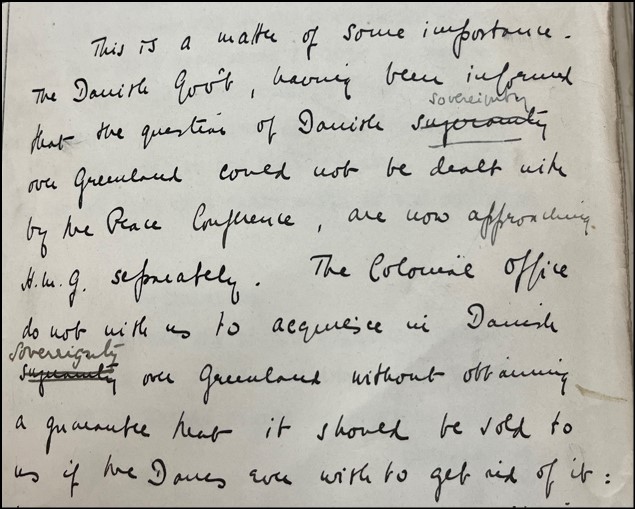

In the wake of the war Denmark wanted all the leading victorious powers to agree. From the internal discussion in the archive records it is clear that there was some unease within the British state, particularly the Colonial Office (CO). This was largely because of potential future implications for Canada, a neighbour to Greenland and at that time a dominion within the British empire.

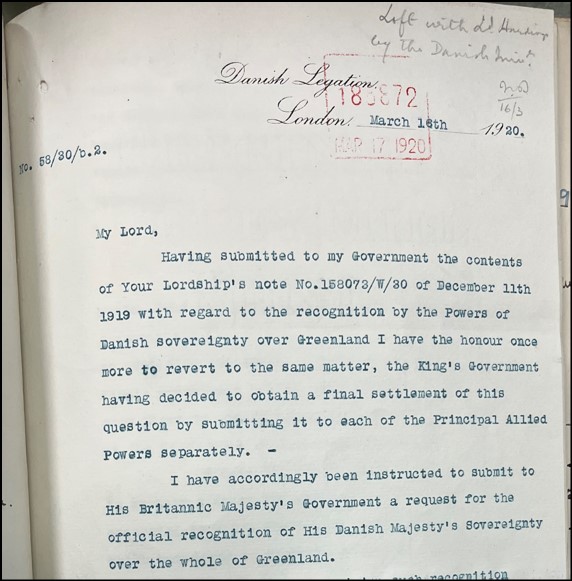

The Danes wanted to raise the issue at the post-war Paris Peace Conference in 1919, but were persuaded not to. In 1920 they formally asked for recognition.

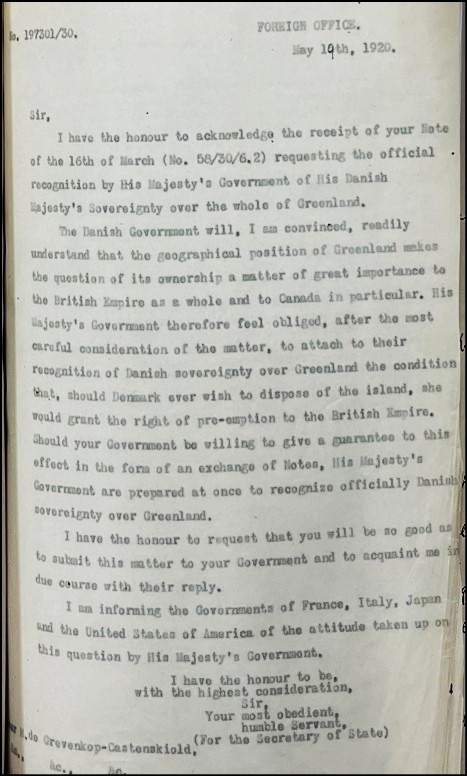

In line with the wishes of the Canadian government, who had been consulted, the Foreign Office informed the Danish ambassador in London that the UK would only recognise their complete sovereignty over Greenland on one condition: that ‘should Denmark ever wish to dispose of the island, she would grant the right of pre-emption to the British Empire’.

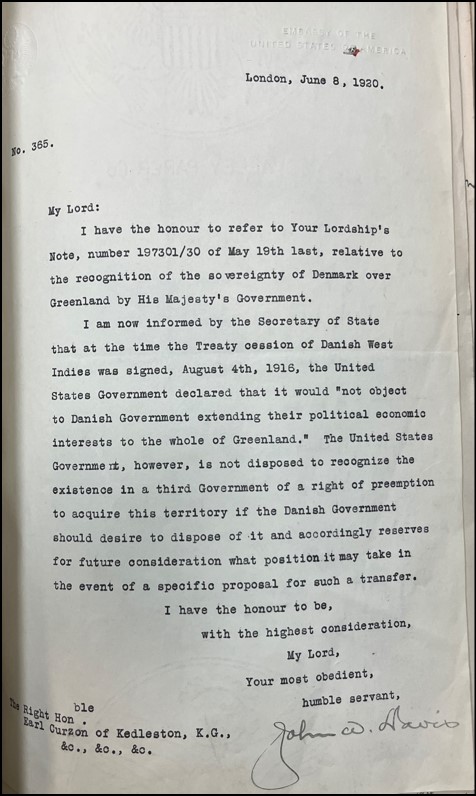

This didn’t go down well with the United States government, who were notified. The US ambassador to London John W Davis wrote to the Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon to say that his government ‘is not disposed to recognise the existence in a third government of a right of pre-emption to acquire this territory if the Danish Government should desire to dispose of it’.

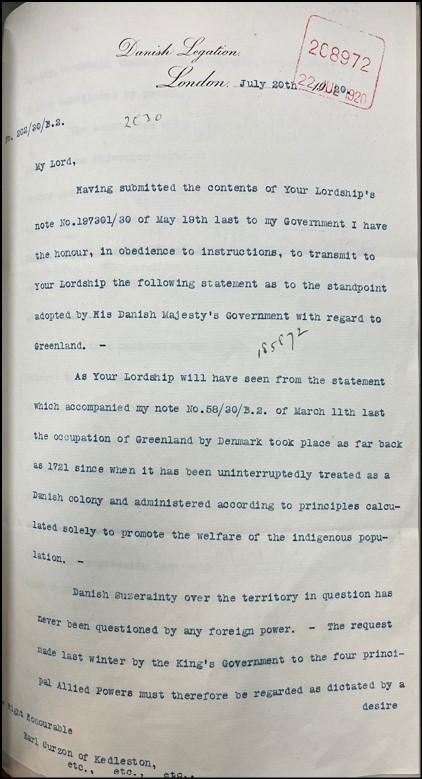

More importantly, the guarantee which the UK wanted didn’t prove acceptable to the Danes.

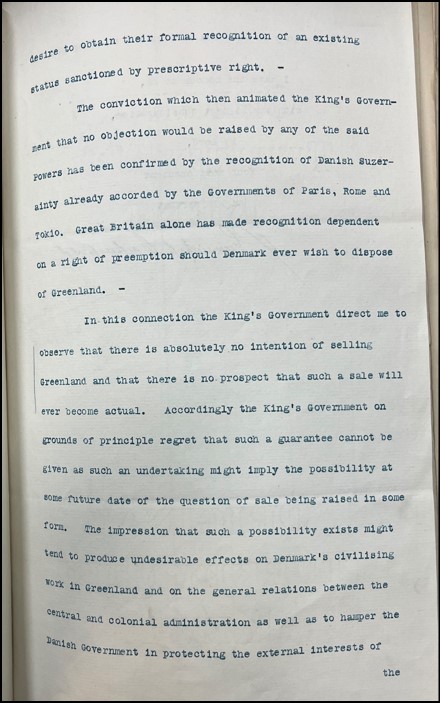

The Danish ambassador replied, stating: ‘The King’s government direct me to observe that there is absolutely no intention of selling Greenland and that there is no prospect that such a sale will ever become actual. Accordingly the King’s Government on grounds of principle regret that such a guarantee cannot be given as such an undertaking might imply the possibility at some future date of the question of sale being raised in some form.’

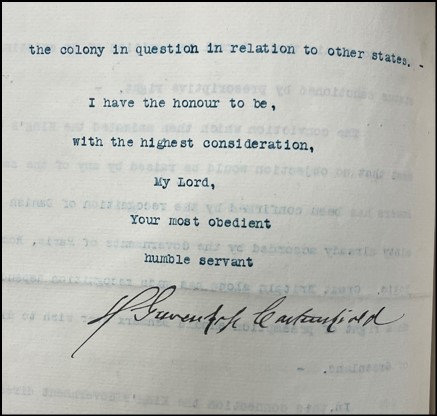

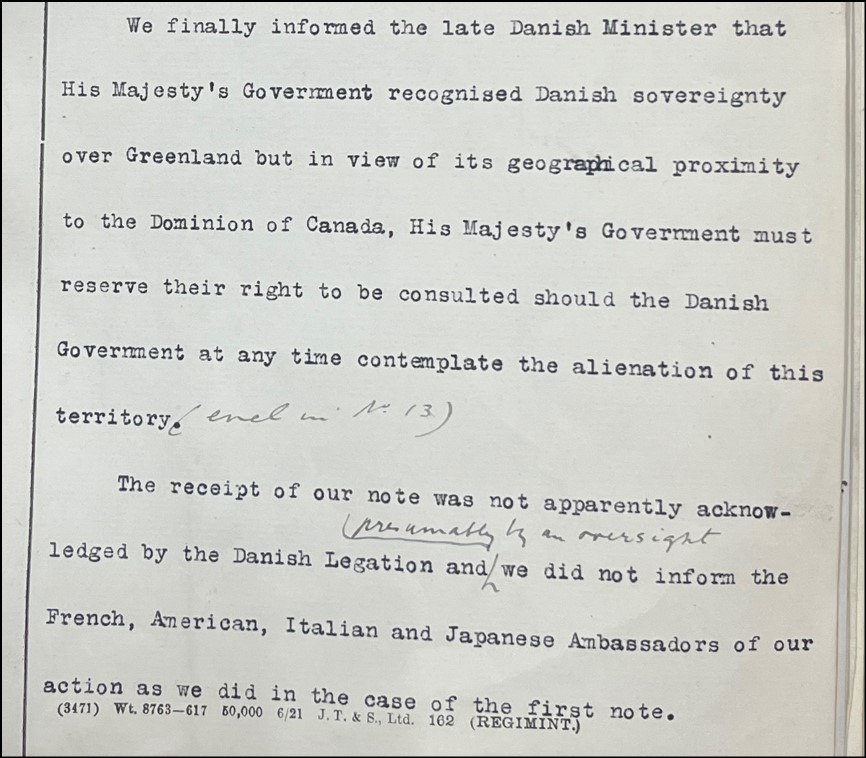

The British then felt they had no alternative but to retreat to a much weaker backstop position, which was agreed with the Canadian government. This said only that ‘His Majesty’s Government must reserve their right to be consulted should the Danish Government contemplate the alienation of this territory’. (I couldn’t find a copy of the original message in the archives, but did come across this later officially typeset version).

‘Alienation’ here is used in the legal meaning of transferring property rights, rather than the current everyday one of causing disaffection. As it happens, in the latter sense the Danish state has over the decades sometimes gone a considerable way towards alienating parts of the local population, but that’s another story.

Greenland is now semi-autonomous and will hold elections next month, in which the question of full independence from Denmark will be a leading issue. The island is currently dependent on substantial financial support from Denmark, but global warming could bring increased economic opportunities with mining and international transportation.

It looks like the Danes never replied.

One Foreign Office official wrote that this was presumably ‘an oversight’. But possibly the Danes didn’t think that this final British missive merited a response.

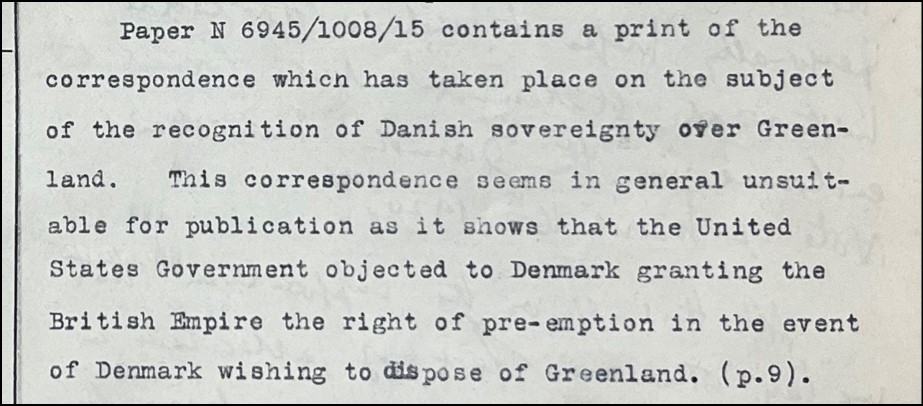

Two years later in 1922 the question arose of whether these exchanges between the governments should be published. This stemmed from an enquiry from the Norwegian government, which was contesting Danish sovereignty over the island in a dispute about fishing and hunting rights.

The suggestion that these confidential messages should be released did not meet with enthusiasm within the Foreign Office, where an official wrote that ‘this correspondence seems in general unsuitable for publication’. There was particular concern not to reveal that the US objected to the British demand for first refusal.

In the file there follows some discussion of whether to release some much more limited information: just the initial Danish request for formal recognition of sovereignty and the final British response. However from the records I could find, it’s not clear what eventually happened and whether any of this was actually revealed to the public at the time.

But in any case it is all revealed here and now. And it’s a very good thing that this paperwork is carefully preserved and made available by the National Archives, so that these questions can today be researched and answered. I hope the person ‘from the government’ found what they were looking for.

My thanks to Liz Evans, one of the independent researchers based at the National Archives, for her specialist expertise and assistance in locating some of these records.

No, Britain doesn’t have first dibs on Greenland Read More »