FOI Fest talk

Here is my 10-minute talk from the FOI Fest conference – It’s a quick tour of some FOI lessons I have learnt – about persistence, phraseology, timing and the FOI requester’s Venn diagram, with a positive note at the end!

Here is my 10-minute talk from the FOI Fest conference – It’s a quick tour of some FOI lessons I have learnt – about persistence, phraseology, timing and the FOI requester’s Venn diagram, with a positive note at the end!

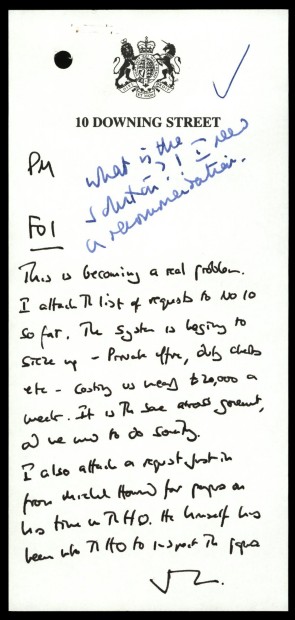

New disclosures from the National Archives reveal how ministers and officials struggled with the freedom of information system when it came into force in 2005.

“This is becoming a real problem” – that’s what a top Downing Street adviser told prime minister Tony Blair about FOI, just a few weeks after the law to open up the state to more scrutiny had come into force at the start of 2005.

Government files just released by the National Archives shed new light on how ministers and officials in Blair’s administration coped with the new public right to make requests for government documents, with their reactions varying from compliance through unease to outright hostility.

This particular memo was written in February 2005 by Jonathan Powell, who was then Blair’s chief of staff and today is still at the heart of power, as the current government’s national security adviser.

He told Blair: “The system is beginning to seize up – Private office, duty clerks etc – costing us nearly £20,000 a week. It is the same across government, and we need to do something.”

The prime minister replied: “What is the solution?! I need a recommendation”.

The government clearly found some of the initial rush of requests to be uncomfortable. In the following year they proposed new regulations to make it easier to reject FOI applications, but these plans met a lot of opposition and were abandoned.

Several years later, after he left office, Blair complained in his memoirs that civil servants had failed to warn him of ‘the full enormity of the blunder’ that in his view FOI proved to be. Powell also was later publicly critical of FOI, writing that ‘policymaking, like producing sausages, is not something that should be carried out in public’.

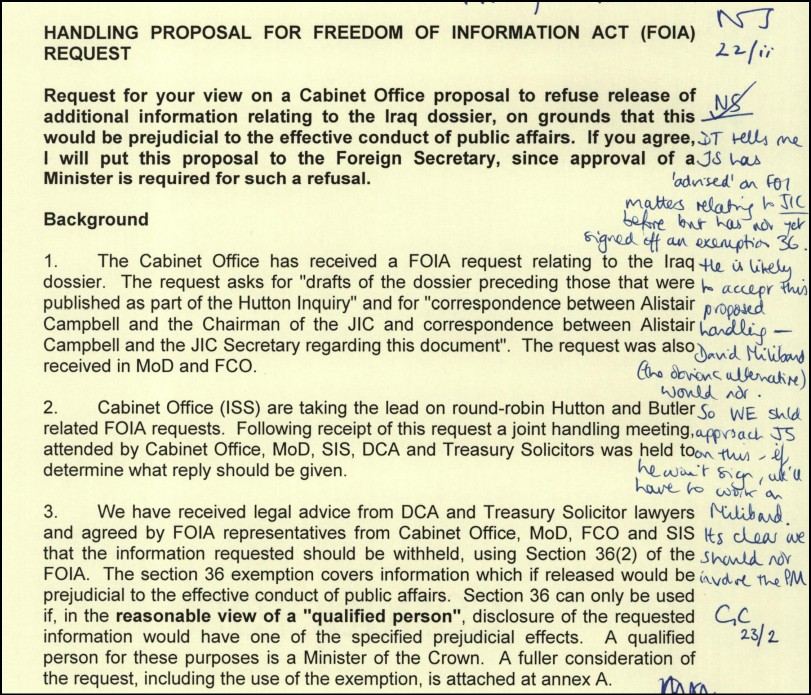

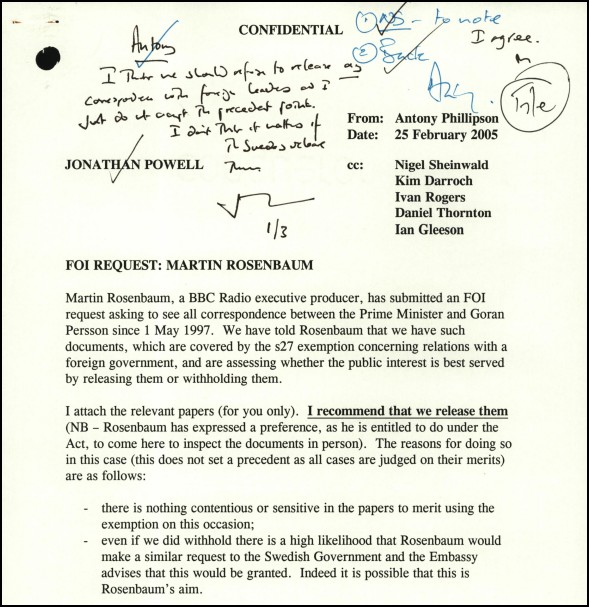

These files, which have been published under the 20 years rule for releasing old government records, also show how civil servants dealt with some of their first FOI cases.

They reveal how officials who did not want to release certain material relating to the Iraq war discussed which minister to approach for sign-off. They decided to ask the Foreign Secretary Jack Straw as they expected he would agree with their planned refusal, as opposed to the Cabinet Office minister David Miliband who they thought would not go along with this. An official added that if Straw wouldn’t comply, ‘we’ll have to work on Miliband’. Straw did.

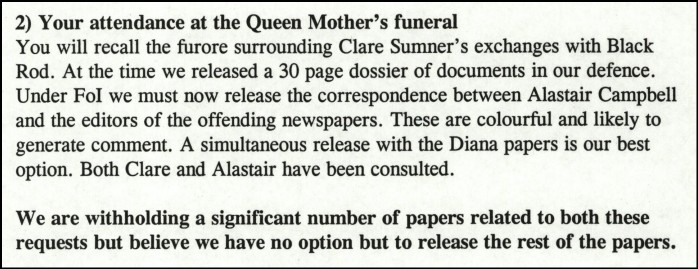

Other examples provide evidence of reluctant information releases which were enforced by the FOI law, as in this memo which an official sent to Blair.

I was particularly interested to find discussion of how to respond to one of my early FOI requests – for correspondence between Blair and the Swedish prime minister, Goran Persson. I’d already obtained some of this from the Swedish government, which had a greater culture of openness, and wanted to see what Downing Street would supply in comparison.

Blair’s private secretary for foreign affairs, Antony Phillipson, recommended giving me the material, which he said contained nothing contentious. But he seems to have been overruled by the chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, who was worried it would set a precedent. Powell wrote that he was opposed to releasing any correspondence with foreign leaders.

So this information has now finally been released by the UK government over 20 years after the Swedish government disclosed it.

It includes the letter Blair sent to Persson to say ‘thank you for Sven’. This was in the wake of the England football team beating Germany 5-1 in the World Cup qualifiers in 2001, an early triumph for the side’s new Swedish manager, Sven-Goran Eriksson.

I was once told by the then Information Commissioner Richard Thomas that Downing Street staff had informed him that they couldn’t send me this amusing but harmless brief handwritten note, which I had written about for the BBC after I obtained it in Sweden, as they hadn’t kept a copy of it. Yet funnily enough, here it is in their files.

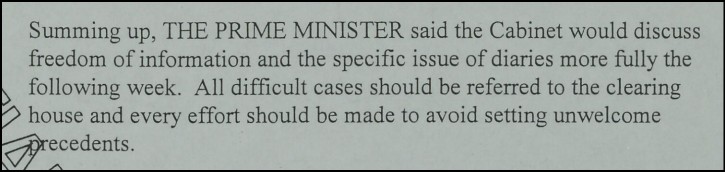

The released documents also show that many ministers were particularly exercised about FOI requests for their diary information, such as who they had held meetings with.

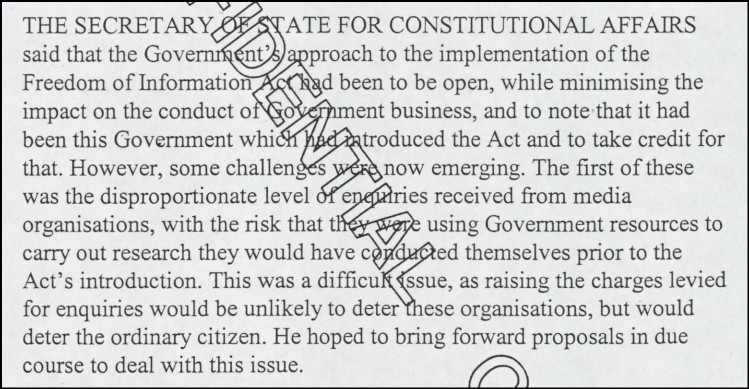

Policy on this was discussed extensively in correspondence between departments. The topic also featured prominently in cabinet meetings during the early months of FOI, as is disclosed in the 2005 cabinet minutes which have also just been released.

The cabinet minutes also give a broader view of how the new FOI system was regarded within ministerial circles, often with concern rather than pride.

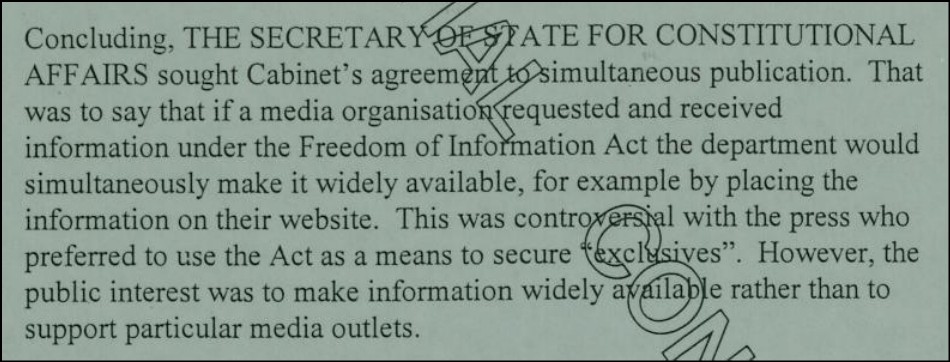

It is interesting to note that the cabinet minister responsible for FOI, the Constitutional Affairs Secretary Lord Falconer, was keen to get departments to publish FOI disclosures on their websites at the same time as giving the information to the requester. This was particularly in the case of the media.

Falconer did not appear to be happy generally with the media’s use of FOI, as he told the cabinet on another occasion.

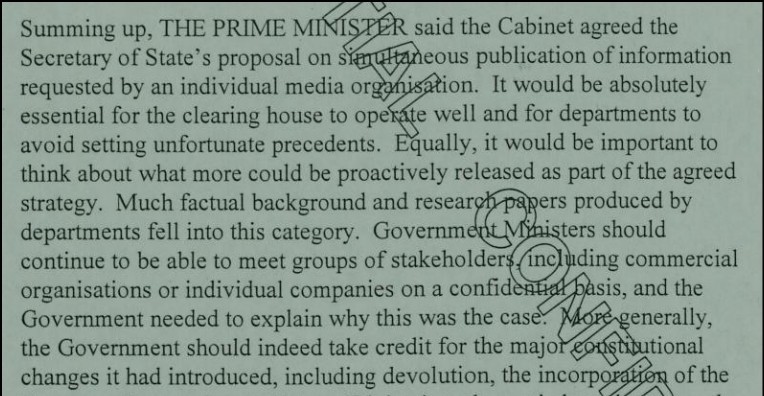

And finally, just before FOI came into force, this is how Tony Blair summarised matters to the cabinet, several years before he announced he was a ‘nincompoop’ for introducing the law.

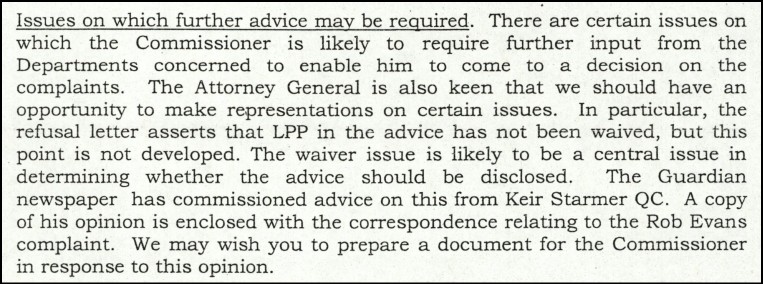

And one more thing. I wonder what Keir Starmer was saying back in 2005, in a legal opinion commissioned by the Guardian, on whether certain government legal advice should be disclosed.

Tony, we have a problem Read More »

The Covid Inquiry has revealed how the use of chat apps in government created an unprecedented document trail, along with a temptation to avoid record keeping or to lose/delete records. Ben Worthy (of Birkbeck College) and I have co-authored a piece about this for Political Quarterly – https://politicalquarterly.org.uk/blog/government-by-whatsapp-covid-transparency-and-government-by-text/ .

Covid, chat apps and FOI Read More »

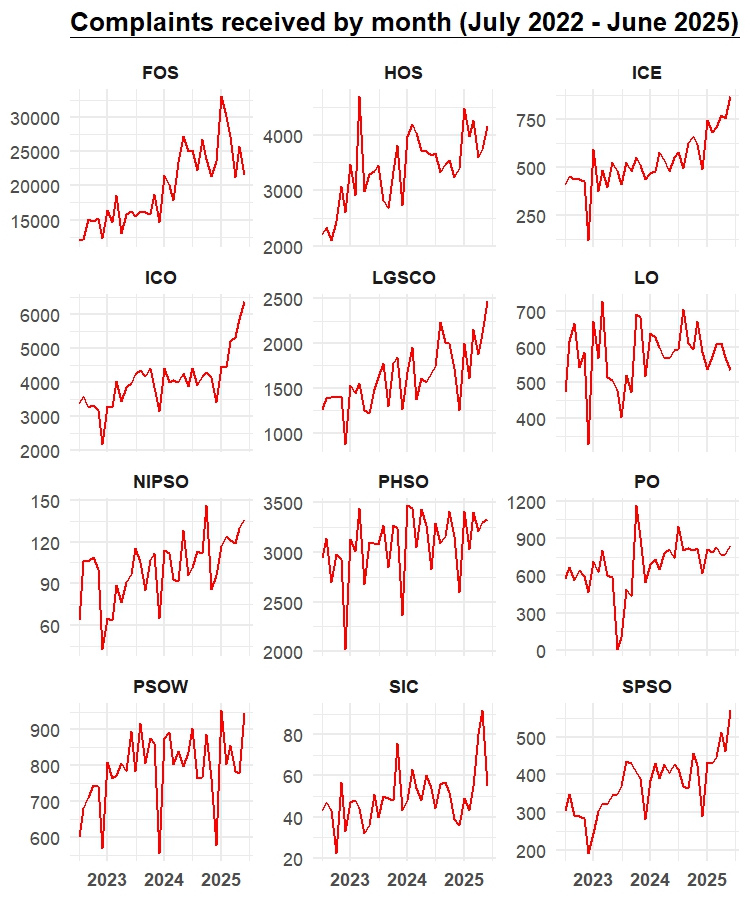

The UK’s major complaints services are receiving increasing numbers of cases to investigate, and the use of generative AI chatbots might be a cause.

How much is generative AI already helping people to assert their legal rights?

Direct research evidence is limited, but one indicator could be that (according to data I’ve obtained) the UK’s main complaints services have seen a recent upsurge in the numbers contacting them.

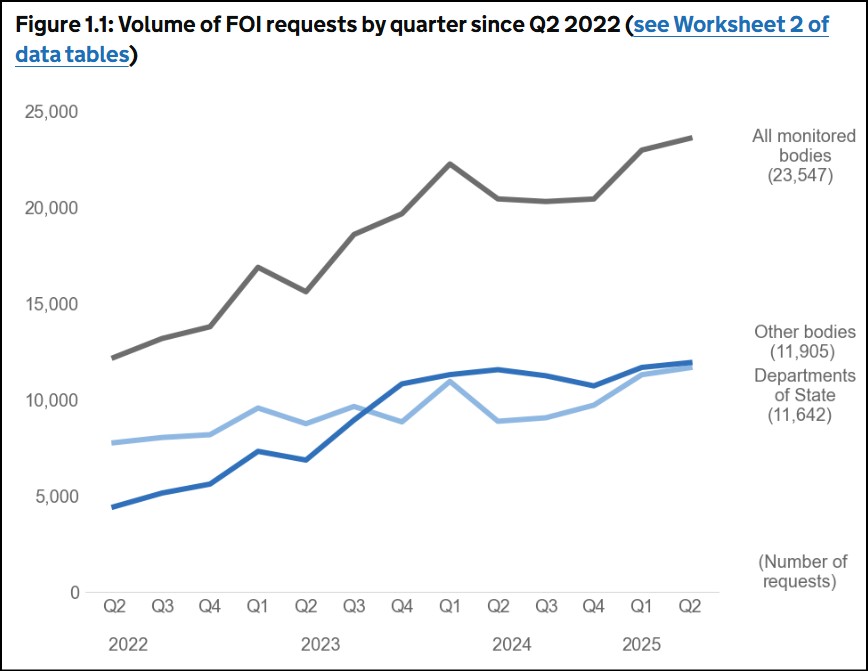

This mirrors the latest official freedom of information statistics which show a significant increase in the level of FOI requests to central government, another civic right.

AI chatbots may be lowering the barriers for ordinary citizens to pursue their grievances over how they’ve been treated by a public authority or commercial company.

On the other hand AI systems are not always used sensibly, while the greater volumes are increasing the demands on those at the receiving end.

I made FOI requests to establish the monthly figures for new cases over the past three years from a dozen authorities which investigate complaints from members of the public, such as the Financial Ombudsman Service and the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman.

The charts below show the three-year pattern in the level of complaints they each received per month. (For further explanation see the notes at the end.) There are lots of ups and downs in each case, but a broad overall trend seems clear.

While none of these bodies seems to have conducted a formal analysis of the role of AI in the increases they are facing, anecdotally within the sector there is talk of the rapidly growing use of AI tools as being a major contributory factor.

The same is true within the FOI community, where some practitioners believe AI is boosting requests.

The next chart is taken from the latest government FOI statistics published last week, and shows what has happened to numbers of FOI requests to central government bodies over the past three years.

The evidence of AI playing a role in all this is circumstantial and anecdotal, but in my view it would be surprising if it wasn’t true. If you make something easier for people, and tell them how to do it, they will do it more often. A little experimentation confirms that popular chatbots will explain how best to raise complaints about failings in services and which organisation to direct them to, and conveniently offer to supply a draft or template for use.

While I’m not aware of any similar research in the UK, one American study last year reported that 18 percent of complaints to the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau had evidence of text generated by an AI large language model.

Nevertheless there could also be other possible causes involved, such as perhaps a more general willingness to complain or more to complain about, as well as the specific factors that would significantly affect individual services.

It seems likely that younger and more tech-savvy citizens would be the earlier adopters. But the US experience suggests that possibly the use of AI in this way is also particularly helpful to people who are less proficient in English.

However the lazy or careless use of AI can hinder rather than help complainants. Last week the Information Commissioner’s Office rather sarcastically rebuked a requester for an internal review application which contained inaccurate statements. The ICO suggested the requester had relied on AI and added: “We advise that any AI generated material is verified before including it in your responses.” (This was spotted by the FOI trainer Tim Turner).

Collating these raw numbers leaves open the question of whether AI-assisted complaints are more or less likely to be effective.

But either way the increased number of complaints may present difficult challenges for these organisations, who will have to cope with the extra workload and prevent the build up of backlogs, possibly without the benefit of extra resources.

In due course AI tools may also help them process complaints more efficiently, in ways that some have already started to develop. However there are serious doubts about both accuracy and public acceptance for automated decision-making.

Notes

Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) handles consumer complaints about financial services.

Housing Ombudsman Service (HOS) deals with residents’ complaints about social housing in England.

Independent Case Examiner (ICE) reviews certain complaints about state benefits and financial support.

Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) covers data protection and freedom of information complaints. My chart amalgamates the figures for these two aspects of its work.

Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman (LGSCO) investigates complaints about councils and adult social care in England.

Legal Ombudsman (LO) handles complaints about legal services.

Northern Ireland Public Services Ombudsman (NIPSO) investigates complaints about public bodies in Northern Ireland.

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) deals with complaints about UK government departments and the NHS in England.

Pensions Ombudsman (PO) covers pension schemes. The dramatic blip in the chart for mid-2023 is because for a period its online submission form was not available, followed by a rush of complaints when it returned.

Public Services Ombudsman for Wales (PSOW) handles complaints about Welsh public services.

Scottish Information Commissioner (SIC) covers Scottish freedom of information cases.

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO) deals with complaints about Scottish public services. And on a side note, they responded to the FOI request which I submitted at 5pm one day by sending all the requested information at 1030am the next morning – so well done to them for the efficiency of their FOI operation.

My full dataset can be downloaded from here.

Generative complaints Read More »

An edited version of a presentation I gave last month for staff at the Information Commissioner’s Office about my perspective on FOI and the ICO. Many thanks to the ICO for asking me to address them.

Thank you very much for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to have this opportunity to share my thoughts on freedom of information from the user’s perspective.

That perspective goes back about 20 years or so, because I’ve been making FOI requests since the law came into force in 2005, primarily as a journalist. Before that I made requests under the previous system, the Code of Practice on Access to Government Information, a much weaker system than the FOI law we have today.

During my time at the BBC, I specialised in using FOI, both submitting requests myself and advising and training other journalists on how to use the law effectively. I left the BBC around four years ago, and since then I’ve written a practical guidebook for FOI requesters.

So over the past two decades I’ve seen a lot of FOI in practice, and when people ask me for an overall verdict on FOI – is it working well, or not? – I have sometimes described it as a ‘tale of two giraffes’.

Of the two giraffes photographed in this slide, one is in London Zoo, and the other is in Whipsnade Zoo in Central Bedfordshire. Three years ago I was doing some research into zoos, and I asked for the latest inspection reports on these two zoos, which should be a very simple FOI request.

Central Bedfordshire Council sent me the latest inspection report on Whipsnade within an hour. It was absolutely the way FOI should work.

Westminster Council, the council responsible for London Zoo in Regent’s Park, didn’t reply. After 20 working days. I sent them a chasing email. They didn’t reply to that. I had to complain to the ICO, and the ICO – thank you very much – did the usual thing of sending an email saying you must reply within 10 working days, and eventually five months after my request I got the report from Westminster.

So what one public authority had been able to do within less than an hour, it took another public authority over five months and the intervention of the regulator.

In other words, sometimes FOI works very well in practice, sometimes it works very badly. And obviously there’s also a lot of circumstances in between those two extremes. But the key point is that the experience of FOI as a requester is that it’s very varied. There’s both a positive side and a negative side.

The positive

Taking the positive side first, and looking back over the last 20 years, one of the very good things is the way that FOI has become well established as a tool that a lot of people use successfully.

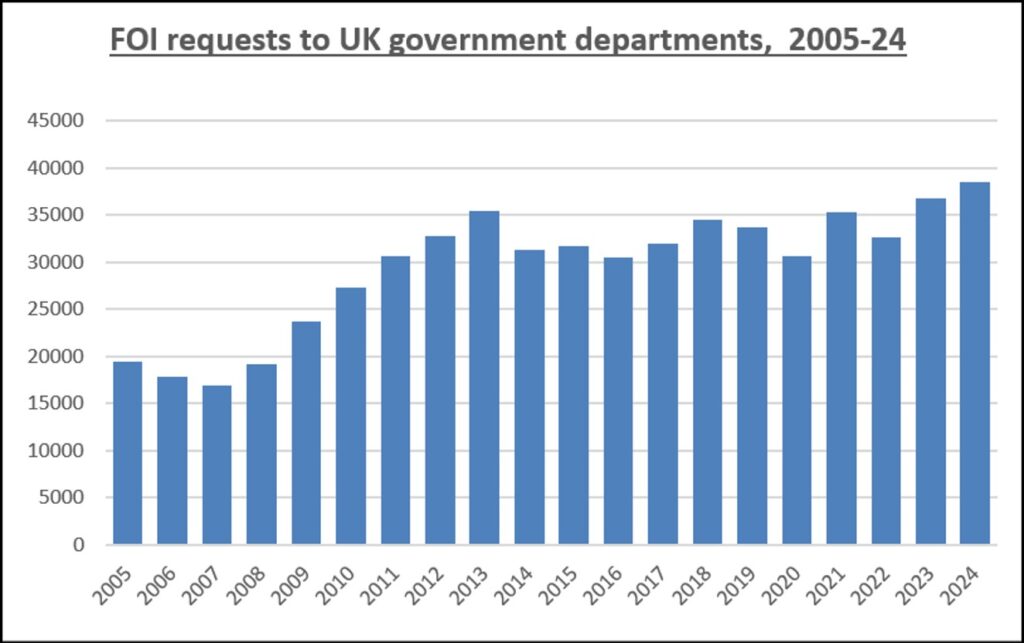

This is a chart which I’ve compiled from government statistics. I don’t think anybody else, by the way, is analysing these annual statistics in the same way that I do, keeping track of them over every year going back to 2005. This shows how in terms of central government departments, for the first few years the number of requests increased quite steadily until about 2013. Since then the numbers have been fairly steady over the past 10 to 12 years or so, maybe 35,000 FOI requests annually to government departments.

As you know we’ve only got statistics for central government bodies. So this is only a very small sample of FOI requests. Yet even so it’s one way of showing that FOI has become well established.

However, that fact obviously hasn’t gone down well with some people. For example, Tony Blair, who said that introducing FOI was like giving people a mallet to hit him over the head with, and that it was one of his two biggest mistakes. He famously wrote these words in his memoirs about the introduction of FOI by his own government: “Freedom of Information. Three harmless words … You idiot. You naïve, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop … I quake at the imbecility of it.”

He’s not the only prime minister who disliked FOI. David Cameron complained about it. Theresa May was more measured in her memoirs, but also had criticisms. And Liz Truss said in her memoirs: “Constant questions about who you’ve met and why … innocent meetings are privy to the press and often deliberately misconstrued.” She does, however, from her point of view, get the chance to blame Tony Blair for it.

What I think about these remarks is that actually they show in a way that FOI is working, at least in some cases. FOI should sometimes be uncomfortable to people who hold positions of power. That’s part of the point of it. If people in power were always very happy about the way that FOI worked, then it wouldn’t really be doing its job. So these quotes from former prime ministers don’t put me off FOI, to my mind they strengthen the case for it.

It’s really quite striking how FOI has reached the level of use and acceptance where it would be pretty politically impossible for a government to seek to weaken the law significantly.

We can see what happened when sometimes they have tried to take certain steps in that direction. For example, the Cameron government set up a review, a Commission on Freedom of Information, which included people like Jack Straw and Michael Howard, former politicians who were thought to be very sceptical about FOI. I think the government at the time was probably hoping that this review would report and pave the way for some restrictions on FOI to be introduced.

But actually when the review looked at how FOI was working in practice (and I’ve got to say full credit to people like Jack Straw, who I know from my own conversations with him had had doubts about FOI), it concluded that the law was generally working well, that it enhanced openness and transparency, and there was no evidence that it needed to be altered. It came down against the suggestion that was around some time ago of introducing charges for FOI requests. In fact, the review even said that in some cases the right of access should be increased.

FOI has become well established, it’s difficult to change in principle, and it works well in practice for many people.

So what is the point of FOI? It’s not to hit Tony Blair on the head with a mallet. As far as I’m concerned, primarily as a journalistic user, its purposes are to find out the truth, to hold power to account, to expose wrongdoing, and to give the public useful information.

There are journalists who’ve made a lot of use of FOI, and others who do so more occasionally, who are trying to achieve these kinds of aims. If we look at a recent list from a website that aggregates news stories, which I searched for freedom of information stories, the selection here is about London’s dirtiest streets, Thames Water (that must be an environmental information request), banks and fraud reports, stories about universities, others about councils, a wide range of themes.

When I was at the BBC we did go to some lengths at some times to collate together on the website a lot of FOI stories that had been done across the organisation, and again what this illustrates is the range of different issues covered, a lot of them very local – health stories, stories about a particular NHS trust, often very much of use to people in the local community, police stories, home affairs, politics stories about what councils are doing, transport stories. One could go on, but it shows the tremendous wealth of topics that FOI enables journalists to find information about in the public interest.

So to give some context about journalistic use of FOI, what do journalists get from FOI requests?

First of all, FOI might directly get the news story – the FOI disclosure in itself is the story, the headline.

But that’s not always the case. Sometimes for us FOI is a piece in a jigsaw, it’s an element in the story. That’s sometimes because you have a case study and FOI gives you overall statistics or context. Sometimes it’s the reverse, you might have some overall context already, but with the use of FOI you can get information about particular examples that help to fill out the story.

Sometimes FOI obtains background information. It doesn’t end up getting reported directly, but it points you in certain directions. It enables you to decide what you’re going to research, it informs questions to put to people in interviews, it helps with how to find out stuff from contacts, and so on.

And of course sometimes you get nothing useful whatsoever. All of us who’ve put in a number of FOI requests have sometimes found that the outcome was nothing of any use.

To give some examples of all of this, here is a story I did some time ago when I was at the BBC about Prince Charles, as he was then, urging Tony Blair to meet campaigners against genetically modified food. Charles doesn’t like GM food and he was lobbying Blair as prime minister about the issue. This fits into the example of the disclosure as the news story.

I have to say on this example that it took me two years to get this information out of the Cabinet Office, and it took four rulings from the ICO at different points in that process. I’m grateful to the ICO for that, but it also shows the kind of attitude sometimes of the Cabinet Office. For example, first of all neither confirming nor denying that they held the information, then trying to insist it was not environmental information, and so on.

To give a different kind of example, here’s a story where the BBC had some case studies about people who were scammed into paying money to get COVID vaccines. It was the kind of thing that a lot of scammers piled into, trying to get money out of people by sending them bogus messages. But is it a big problem? Well, FOI enabled the BBC to get some kind of national overall context and say there’s over a thousand reports, people have lost nearly £400,000 to scammers through this scam, so it is a significant thing. That’s an example where FOI is a piece in the jigsaw, you’ve got the case studies and then you’ve also got overall statistics.

Next is a different kind of example of a story I did once, and this is one of my favourite examples of the success of FOI, for reasons which I’ll explain.

This is about which makes and models of cars are most likely to fail MOT tests. When I first requested this data from a Department for Transport agency, I was told that this information would not be released to me under the commercial Interests exemption, presumably because it would be damaging to the commercial interests of people who sold cars that didn’t do well. Again, I appealed to the ICO, and the ICO again ruled in my favour, forcing the Department for Transport agency to release this information, which I regard very much as in the public interest, as useful to potential car purchasers, knowing which cars are most likely to do well in MOTs and which aren’t.

This information is now released annually routinely as open data. In other words, what for 18 months the Department for Transport told me was so confidential it could not be disclosed is now released routinely and proactively. It’s a very good example of the benefits of FOI, transforming information that was previously secret into something which is released as a matter of routine.

Another instance of this is food hygiene reports, where again we had councils refusing to release food hygiene reports, and where again the ICO stepped in and ruled that it’s in the public interest for the public to know which food outlets have good food hygiene and which don’t. And this has now become information which the Food Standards Agency releases routinely as a matter of course. We have ‘scores on the doors’, so you can see on the outside of a restaurant how it’s doing.

That transformation has enabled journalists to do this kind of story – how do restaurant chains compare? To give the quick summary, if you want to go to a place with good food hygiene consistently across the country, when we did this study Nando’s had a satisfactory score everywhere. So you can’t say you don’t get useful information out of this kind of talk.

Another example I want to share illustrates the kind of information I think of as practically useful. This was a graphic I generated based on data from individual hospitals, showing A&E waiting times by hour of day and day of week. Each line represents a different hospital. The pattern is clear: if you turn up at midnight, any day of the week, you’re likely to wait much longer than if you arrive around eight o’clock in the morning.

That’s useful information, and yet it wasn’t being published at that level of detail by NHS England, even though it was collecting the data. I had to request it through FOI. Without the law, I wouldn’t have been able to obtain it.

The negative

So that’s some of what I see as the positive potential of FOI, and what I and others have achieved with it, but on the other hand FOI doesn’t always work well. Journalists frequently complain about delays and obstruction. Here’s a headline from the Press Gazette, the news trade website: ‘Freedom of Information in the UK sinks to new low’. This story is from 2024, last year, but you could probably find a version of that story in the Press Gazette every year. Because FOI still all too often doesn’t function as it should.

I first want to make a general point. Part of the problem is a broader shift in official attitudes. In the past there were more people in positions of power, contrary to the views of Tony Blair, stressing the benefits of openness and transparency. In the early years after the law came into force in 2005, there was rhetorical support from government for openness. Lord Falconer, the minister responsible for FOI at the time, attacked the ‘culture of secrecy’ – you don’t hear government ministers now saying that kind of thing.

Then under the Cameron government, the Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude was very keen on open data – which is not the same as FOI, but is part of a wider transparency agenda.

Again we don’t hear that from ministers today, that rhetoric about the benefits of transparency and openness. And this climate does have an impact on how public authorities behave, and in some respects they are more resistant to releasing information.

Here’s an example. Early on in the FOI period I obtained documents showing how the Metropolitan Police Special Branch had monitored the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the UK over 25 years. They were released in 2005. There is absolutely no way the Metropolitan Police would release that information today. In the early years of FOI they were generally more committed to transparency, and it’s an example of how things have deteriorated.

Sometimes I’m accused of being too cynical, so let’s take a look at what the chief executive of the Environment Agency, Philip Duffy, said at a conference last year: “I see these letters and these FOI requests and I’ve got great volumes of them, and I see local officers going through contorted processes not to answer when they know the answer and it’s embarrassing.”

This is a clear statement from the chief executive of the Environment Agency about how his officials behave, trying to avoid releasing embarrassing information. This is obviously a completely unsatisfactory state of affairs. It’s not only the Environment Agency, in some ways what we have here is Philip Duffy being more honest about how FOI sometimes operates than other public authorities often are.

Another example: a slide from internal Cabinet Office training on FOI. It says: “If you don’t want to appear in tomorrow’s newspapers, consider carefully what you send out.” That’s basically telling people don’t release stuff which is embarrassing, and it’s not what the law says. There’s no FOI exemption in the Act for “Stuff you don’t want to appear in tomorrow’s newspapers”. That should be a totally irrelevant consideration, yet here we have it appearing in the Cabinet Office guidance to staff on how to handle FOI requests.

I do think journalists in particular often have a problem with how their FOI requests are handled. To give just one example of the sort of processes that come into play, the Financial Conduct Authority guidance to staff on FOI explicitly states that approval for journalists’ requests must be “obtained from press office”. It’s very far from being the only body where this is the case, very far indeed, and I see two problems with this. First of all, it inevitably increases delay, because the reply has to be checked by the press office. But secondly, for people who work in the press office, their job is to protect the reputation of the organisation where they’re working. That is entirely separate from FOI considerations and they should not be involved in approving the answers to FOI requests.

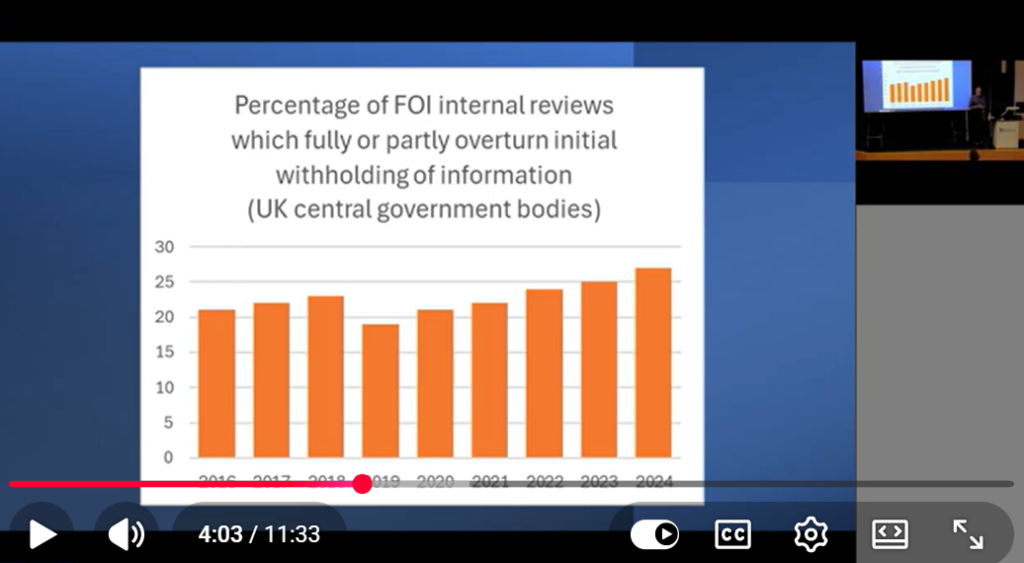

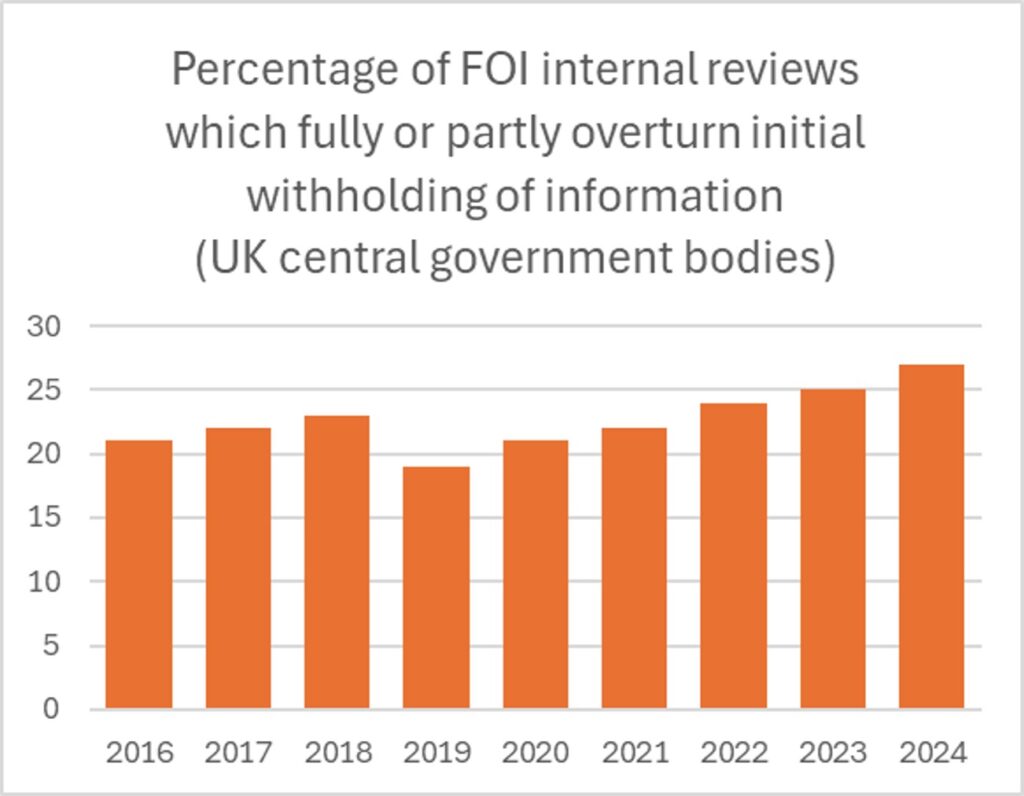

This is another statistical analysis I’ve done, of how often internal reviews change initial refusals. Again, as far as I’m aware, I’m the only person who is analysing the statistics issued about central government FOI requests to this extent. This chart shows how often internal reviews overturn, partly or entirely, an initial refusal from a government department that information should be withheld.

It’s only because we have statistics for central government that we can do this. We don’t know what the position is for all sorts of other public authorities. But what we can see here is that maybe 20 to 25 percent, and perhaps increasing, of internal reviews overturn an initial refusal, partly or entirely.

You can look at this in two ways. One is to say that internal reviews are actually doing their job, scrutinising the initial decision. But I also think that this rate is surprisingly high, suggesting that very often at the initial stage people are refusing FOI requests in ways that they should not be. This isn’t even the ICO getting involved. This is just somebody else in the same organisation saying you should have released it, and I think it points towards an initial level of obstruction in some cases.

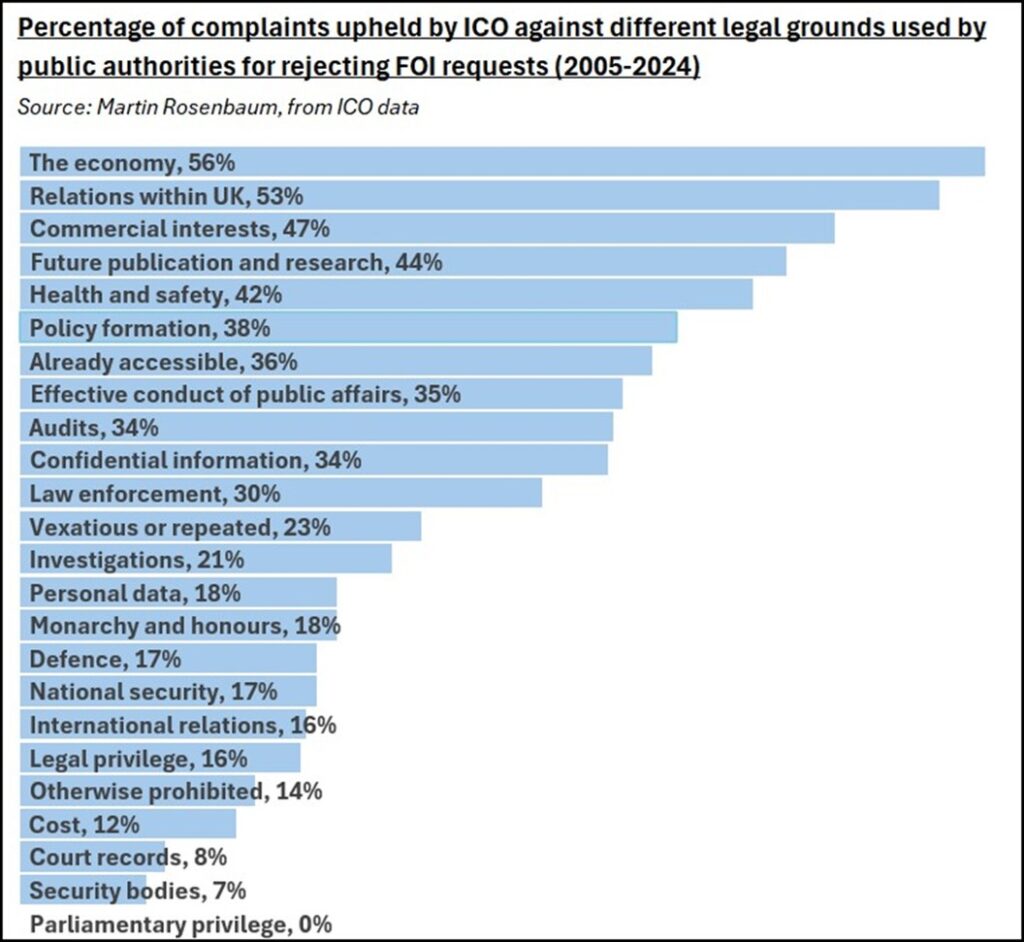

Now let’s look at how often the ICO overturns decisions made by public authorities. This is an analysis I did based on a dataset going back to 2005 which the ICO released last year. I don’t know to what extent this kind of analysis is done internally within the ICO or not.1

What I find really striking about this is how for some of these exemptions, the ICO overturns them so often. Taking the ones at the top, the economy and relations within the UK are not so often used, but commercial interests is a very frequent exemption used by public authorities to turn down requests. Yet of the cases that have been appealed to the ICO, basically in half of them the ICO has overturned it.

And there are other exemptions – future publication, policy formation and so on – where the ICO is very frequently overturning their use. What that really points to is a systemic issue that these exemptions are being overused by public authorities. And what the ICO in my view needs to do is draw attention to that and say there is a widespread problem of the overuse of certain exemptions.

I’m aware that the ICO has issues about resources and its level of casework. So if authorities could be stopped from overusing those exemptions, then that will be a way of reducing the level of casework that the ICO gets, and this is another reason why the ICO should be vocal in flagging the systematic overuse of certain exemptions.

The ICO

As I’m talking to the ICO, I should tell you my view of the ICO. This is what I wrote in my book: “Despite problems of resource constraints and significant delay (and the fact that I sometimes disagree with its decisions)” – we’ll come onto that later – “its existence is one of the strengths of the UK’s FOI system”.

When I’ve done training for journalists, this is one of the points that I make, that it’s a strength of the UK system to have an independent body which can overrule public authorities. That’s not the case in some other countries, and the ICO’s role is very valuable.

Let’s take some aspects of its FOI work in more detail. On delay, I very much welcome what the ICO has done over the past couple of years or so to speed up its consideration of complaints about FOI.

In contrast there was an extreme example back in 2009, when the ICO ruled in my favour on releasing the minutes of a Thatcher cabinet meeting about the Westland crisis, where it took the ICO four years to reach that decision. That’s ridiculous. It’s an extreme case, but when the ICO takes that sort of time, then public authorities have tremendous incentives to boot issues into the long grass, turning down requests for information on the basis that by the time the ICO rules, no one will care about it. A lot of progress has been made in speeding up the ICO’s procedures, and it’s vital that it doesn’t deteriorate again.

The fact that the ICO now prioritises certain FOI complaints with significant public interest is also a welcome and valuable step which enables the most important cases to be dealt with most quickly. Maybe the threshold for prioritisation is a bit too high and probably more cases should be prioritised, but in general it’s absolutely right to have done this.

I’m also very pleased by the way that the ICO is now taking serious regulatory action against recalcitrant public authorities. For example, the enforcement notices and practice recommendations served on numerous police forces recently and rightly, because the performance of the police in FOI terms has often been very bad, as has also been the case for various government departments, certain NHS bodies and so on.

It’s much more effective for the ICO to take this kind of regulatory action, issuing enforcement notices, than the kind of situation that we used to see beforehand.

Take this example that I wrote about the Cabinet Office. You would have this flow of decision notices from the ICO referring to Cabinet Office delays as being unacceptable, unhelpful, extreme, protracted, considerable, unsatisfactory, excessive, prolonged, severe. One decision notice after another would say this, but nothing ever changed by just issuing decision notices where it says in passing that delays are unacceptable.2

In contrast taking proper regulatory action and issuing enforcement notices is the best way to achieve change from the most recalcitrant public authorities, and I’m very glad to see that the ICO has been doing that.

However, I’m not going to say that everything about the ICO is completely marvellous. I’m pleased about reducing delays, I’m pleased about the prioritisation, I’m pleased about the enforcement action. But I do think there is an issue about the quality of certain ICO decisions, and there are decisions where the ICO does not really address properly the balance of the public interest.

This includes recent cases where I’ve been successful in appealing ICO decisions to the First-tier Tribunal.

One example involves the House of Lords Appointments Commission and the citations provided for some of Boris Johnson’s appointments to the Lords. In my opinion it’s overwhelmingly in the public interest that the public knows what are the official reasons given for why people are put in a legislative assembly. The tribunal agreed with me on that point3 that the citations should be public. So the House of Lords Appointments Commission was forced to reveal them.

I was disappointed, however, that I needed to appeal to the tribunal in order to achieve this. This is a case where the ICO should absolutely have said it’s in the public interest for this to be out in the open, and people could then assess for themselves the reasons that Boris Johnson gave as to why people should be members of the House of Lords with the right to decide on laws everyone else has to abide by.

That’s one example, and another occurred just last month when the First-tier Tribunal ruled that I should be given information in a Cabinet Office case where the ICO had ruled against me on a public interest test.

The tribunal said: “The tribunal shares the appellant’s view that there is a strong public interest in upholding standards of good decision-making, transparency and integrity in public administration … In the tribunal’s assessment, the withheld material is relatively benign and does not contain candid or controversial exchanges. The tribunal finds that the Cabinet Office’s concern over inhibiting future frank advice is overstated and not supported by the content of the material in question.”4

Here we have another example of the ICO in my view not taking a strong enough stance on where the balance of the public interest lies, and then the tribunal has to step in. That means extra work for me as the requester to appeal to the tribunal, but it’s also extra work for the ICO, which then ends up trying to defend an untenable position at the tribunal, costing a lot of time and money, as well as being against the public interest.

I know there are other cases where the ICO has taken a position which has annoyed the Cabinet Office. But I think it doesn’t do that often enough, and the ICO should be more prepared to stand up to the Cabinet Office on cases like these.

Finally, I wanted to make one other point, and this goes back to what I was saying earlier about the public debate about open government. I’d like to see the ICO now speaking out more about the broad advantages of transparency. We need to be hearing the voice of the ICO more often in public discussion.

To give one specific example, a government policy document issued last year states that it’s going to extend the FOI Act to private companies that hold public contracts, and that the government will take this forward “in due course”. So it’s publicly committed, but we’ve no idea when it will actually do this, or even if it will really happen. It’s not in the current legislation.

This is the kind of thing that in my view the ICO should be talking about now. It should be stepping into this discussion and saying this is an important and valuable change that is needed, because so many services are contracted out in the way that our public sector now operates.5

I’ve left time for questions. Thank you very much indeed.

——————————————————-

1 During the Q&A session afterwards I was told that the ICO does do this analysis itself.

2 On the day after I delivered this talk, the ICO announced it was issuing a practice recommendation against the Cabinet Office due to its FOI delays.

3 ICO staff are keen to point out that the tribunal did not agree with me on everything and upheld some other parts of their decision.

4 The material in question can now be found here, if you want to decide for yourself whether its release will damage free and frank discussion in the civil service in future.

5 In the Q&A I was reminded that the ICO has issued a report on this topic, but the point I made was that this was done back in 2019.

Twenty Years of FOI: A User’s Perspective (My presentation to the ICO) Read More »

On Tuesday June 3 in London I’m giving a talk on how to use freedom of information productively to a Meetup for the London Business Analytics Group. It’s a free and friendly event, open to everyone. So please do come along if you’d like to know more (and do tell others about it) – details here.

Forthcoming talk about using FOI Read More »

After a freedom of information dispute lasting 18 months, I have finally obtained the official reasons Boris Johnson provided with his resignation honours list for giving peerages to Charlotte Owen and Ross Kempsell.

The reasons cited for nominating Owen to membership of the House of Lords do come across as very thin, inadequate and lacking in evidence of relevant achievements. They leave her peerage as a mystery rather than properly justifying and explaining it.

The justification which the former prime minister supplied to the House of Lords Appointments Commission states that Johnson “entrusted Charlotte with engaging the parliamentary party on his behalf and she was essential to maintaining his relationship with them”. He added that “Charlotte was later tasked with helping the new Chief Whip in his role and used her unique knowledge to become a bridge between the Prime Minister and the Chief Whip”.

Johnson’s citation for her also states that “Charlotte led on many sensitive and key projects including advising the Prime Minister and the Chief Whip on suitability for Ministerial appointments during the reshuffle”. No other details of these “sensitive and key projects” are given.

The first part of this citation fits with the notion that she was a junior official with very little responsibility and experience, whose sudden elevation to a peerage was peculiar.

The unevidenced claim in the citation that she led on “many sensitive and key projects” including on advising on ministerial appointments will, I think, come as a surprise to a lot of people working in Downing Street at the time.

The citation added that Owen wanted to advocate for young women who have fallen victim to image based sexual abuse, an issue she has indeed taken up since being in the House of Lords.

The released documentation also reveals that her nomination was supported by the former Tory cabinet ministers Grant Shapps and Chris Heaton-Harris, although not what they said.

The citation for Ross Kempsell is more detailed, giving an account of his work and achievements as the head of the Conservative research department and a special adviser in Downing Street.

The House of Lords Appointments Commission was eventually forced to release this material due to a lengthy freedom of information case I have been pursuing with them.

I am very pleased that the documentation has now been revealed, but it shouldn’t need an argument over 18 months for the public to find out what reasons are officially provided for allocating certain people important political powers.

Members of the House of Lords debate and vote on laws that control the British public’s lives. As a basic principle the public is fully entitled to know what reasons are given for why they have been appointed to rule over us.

The two peers are now known as Lady Owen of Alderley Edge and Lord Kempsell, and have both been active in the Lords after their somewhat unexpected appearance in Johnson’s resignation honours in June 2023.

At the time of the announcement they were 29 and 31 respectively. Owen’s ennoblement caused a great deal of consternation and puzzlement, as there was no evidence of any achievement of hers that could explain it.

She was a junior staffer working in Johnson’s Downing Street operation. Press reports described her as possessing “no views, no achievements, no experience” and as “the most junior person in political history to have received a peerage”, while also alleging discrepancies in her career history.

The disclosure follows a ruling last month from the First-tier Tribunal, which upheld my arguments that releasing this information is in the public interest.

It is the culmination of the dispute between myself and HOLAC, which initially rejected my FOI request in July 2023 for the information held about these two nominees. After HOLAC insisted on its position, I complained to the Information Commissioner and then appealed to the Tribunal.

At the Tribunal hearing, where I represented myself against HOLAC’s extensive legal team and cross-examined Clare Brunton, the secretary of HOLAC who is also head of the honours secretariat in the Cabinet Office, I argued that the process for giving individuals a status as legislators is a vital matter of the public interest.

Those appointed can approve or reject proposed laws, as well as being able to take part in parliamentary debates, directly question ministers, and so on. This entails the need for maximum transparency, so that the process is both legitimate and is seen to be legitimate, and the public can see for themselves whether appropriate procedures are followed.

The First-tier Tribunal’s judgment stated: “We attributed considerable weight to the public interest knowing the PM’s reasoning … Life peers are Members of Parliament with the rights, obligations and influence associated with such an appointment thus enhancing further the weight of the public interest in the PM’s citations.”

The Tribunal dismissed HOLAC’s arguments that releasing the information would damage the honours system and be a breach of confidence.

The full citations disclosed to me are here.

If you are interested in taking an FOI case to the First-tier Tribunal, there is a chapter devoted entirely to this with detailed and thorough advice in my book, Freedom of Information – A practical guidebook.

Why Johnson said Charlotte Owen should get a peerage Read More »

The public can now expect to find out the reasons Boris Johnson officially provided for nominating Charlotte Owen and Ross Kempsell to the House of Lords, due to a lengthy FOI battle I have pursued.

A Tribunal has ruled that the confidential recommendations put forward by the former prime minister for two of his most controversial peerage appointments must be disclosed.

It has just ordered the release of the secret citations Johnson sent to the House of Lords Appointments Commission (HOLAC) for the peerages awarded to Charlotte Owen and Ross Kempsell in his resignation honours list in June 2023.

This is the latest stage in an 18-month freedom of information dispute between myself and HOLAC, which turned down my FOI request in July 2023 for the information held about these two nominees.

The First-tier Tribunal, which hears information rights cases, has now backed the view that releasing the citations Johnson submitted to justify the nominations is in the overall public interest.

It has also instructed that the identity of some public figures who were indicated as supporting Charlotte Owen’s appointment should be revealed.

I’m very pleased by the decision, which is a boost for transparency and democracy. Members of the House of Lords debate and vote on laws that control the British public’s lives. As a basic principle the public is fully entitled to know why they have been appointed to rule over us.

According to HOLAC, citations provide ‘the reasons for nomination’ and a statement of ‘personal and professional background and attributes’.

The two individuals involved are now known as Lady Owen of Alderley Edge and Lord Kempsell, and have both been active in the Lords after their somewhat unexpected appearance in Johnson’s resignation honours.

At the time of the announcement last year they were 29 and 31 respectively. Owen’s ennoblement caused a great deal of consternation and puzzlement, as there was no evidence of any achievement of hers that could explain it.

She was a junior staffer working in Johnson’s Downing Street operation. Press reports described her as possessing “no views, no achievements, no experience” and as “the most junior person in political history to have received a peerage”, while also alleging discrepancies in her career history.

The Tribunal’s judgment published today states: “We attributed considerable weight to the public interest knowing the PM’s reasoning … Life peers are Members of Parliament with the rights, obligations and influence associated with such an appointment thus enhancing further the weight of the public interest in the PM’s citations.”

The Tribunal dismissed HOLAC’s arguments that releasing this information would damage the honours system and be a breach of confidence.

The decision means HOLAC has until 22 January to release the material.

I brought the case to the Tribunal to appeal against the Information Commissioner, who in March this year had upheld HOLAC’s rejection of my request. It shows that it is worthwhile challenging weak decisions from the IC.

The Tribunal has now overruled the Commissioner, following a one-day hearing in October. However it did not back all aspects of my appeal, coming down against the release of the detailed minutes of the HOLAC meetings which discussed Owen and Kempsell.

At the hearing, where I represented myself against HOLAC’s extensive legal team and cross-examined Clare Brunton, the secretary of HOLAC who is also head of the honours secretariat in the Cabinet Office, I argued that the process for giving certain individuals a status as legislators is a vital matter of the public interest.

Those appointed can approve or reject proposed laws, as well as being able to take part in parliamentary debates, directly question ministers, and so on. This entails the need for maximum transparency, so that the process is both legitimate and is seen to be legitimate, and the public can see for themselves whether appropriate procedures are followed.

Earlier this month the Labour government announced that in future the citations to support individual nominations for political peerages will be published. This is also a welcome move towards much-needed greater openness in the appointments system for members of the House of Lords.

If you are interested in taking an FOI case to the First-tier Tribunal, there is a chapter devoted entirely to this with detailed and thorough advice in my book, Freedom of Information – A practical guidebook.

FOI Tribunal orders release of Owen and Kempsell peerage citations Read More »

As Rachel Reeves ponders her forthcoming budget and how to balance raising money against economic growth, one of her self-imposed constraints is her pledge not to raise the rate of VAT. However the impact of taxes also depends greatly on the thresholds from which they apply, even though this tends to get a lot less attention in public debate (as is certainly the case for income tax).

So what about the annual turnover level at which businesses have to register for VAT?

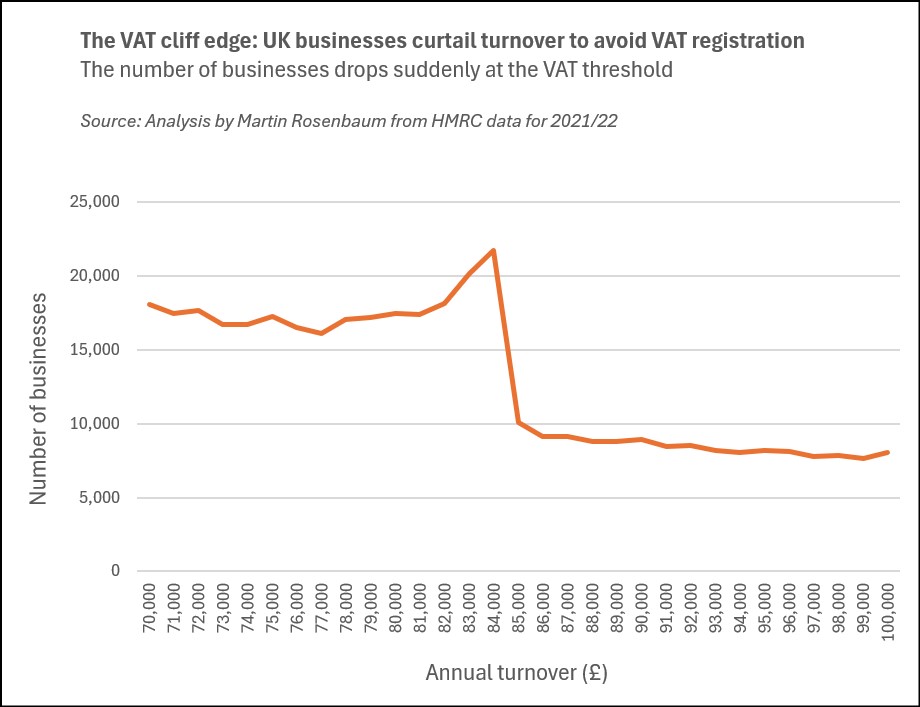

Data I have recently obtained from HMRC under the freedom of information law shows the dramatic impact of the VAT threshold in restricting the growth of some of the UK’s small businesses.

In 2021/22 the UK had 21,752 businesses with annual turnover in the range £84,000-£85,000, just below the then threshold. But there were only 10,096 businesses just over the limit, in the range £85,000-£86,000.

In other words the number of businesses clustered just under the VAT threshold was more than double the number just above, as businesses curtail their activities to remain outside the VAT registration system.

The graph above clearly shows the cliff edge in the data.

Many small businesses are desperate to keep their annual turnover under the VAT level, so that they avoid the bureaucracy and costs of registration and they don’t have to charge VAT to customers, which would make them less competitive. However the consequence is that they then won’t grow further into larger, more successful operations.

For some businesses the VAT threshold functions as a ceiling constraining their growth.

Research by Warwick University in 2022 concluded that earlier data of this kind reflected genuine curtailment of business activity rather than false reporting to HMRC.

This is the latest data available from HMRC, which says that more recent information is still being processed. The current VAT threshold is now £90,000, as the figure was increased by the Conservative government before the general election.

The UK’s VAT threshold is high compared to other European countries which tend to impose VAT registration on businesses at a much lower level. While the UK policy saves many small businesspeople from the compliance burden of VAT, the significantly lower thresholds elsewhere make it less likely that enterprises will be found bunched and held back just under the relevant level of turnover.

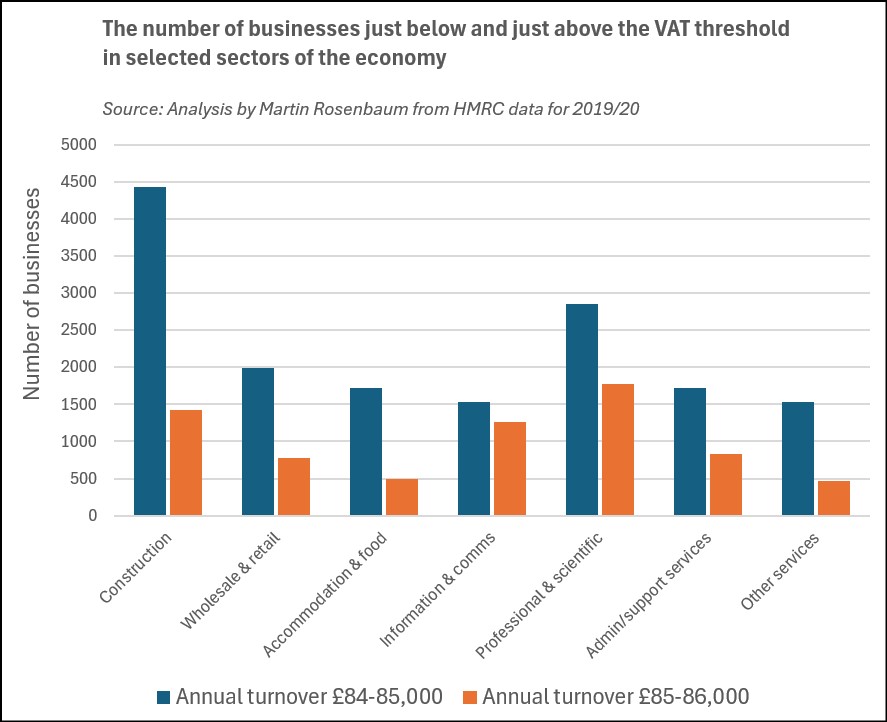

I also wanted to get a breakdown of the data by sector of the economy, to see which kinds of businesses were most affected. HMRC said it could provide this for 2019/20, as it had previously extracted the information involved, but that more recent breakdowns would probably exceed the FOI cost limit.

According to these 2019/20 figures, the most dramatic effect is in the construction sector.

This data shows 4,445 construction businesses with an annual turnover of £84,000-£85,000, but only 1,425 in the range £85,000-£86,000. So the number of construction businesses appearing to have kept themselves just below the limit is over three times the number who grew a little more and just exceeded it.

The chart shows the impact for construction and some other economic sectors with large numbers of small enterprises.

These FOI releases from HMRC constitute the latest and most thorough official evidence of what the tax expert Dan Neidle of Tax Policy Associates has called ‘the VAT growth brake’.

The full HMRC spreadsheets can be downloaded here:

The VAT cliff edge: How the threshold impedes small businesses Read More »

Ever since the Freedom of Information Act came into force nearly 20 years ago, some unhappy public bodies have protested loudly about the resulting ‘administrative burden’. But what is less appreciated is how numerous authorities actually seem to find the law useful – to obtain information themselves.

A few weeks ago Redcar and Cleveland Council issued a statement asking that the new Labour government ‘significantly revises the scope of the act to reduce the burden on councils’.

The particular grievances itemised included the usual targets of FOI applications emanating from businesses and journalists, but the council also focused its ire on ones which came from ‘local/national government’.

Intrigued by this, I asked the council (under FOI, naturally) for details of recent requests from local and national government. And it turned out that there were more than I expected, covering a wide range of council responsibilities. See the list below.

In my view these are entirely reasonable and legitimate requests. If FOI enables councils to find comparable information from their counterparts, which assists with policy development, service provision, budgeting and external contracting, that is not a reason to curtail the law – it is another reason to stress how useful FOI is in contributing to the general public interest.

Incidentally, there weren’t actually any applications from national government departments, despite what Redcar and Cleveland Council claimed. There were however numerous requests from MPs and Peers (or their staff), which the council bizarrely lists as coming from ‘National Government Departments’, but that is obviously not the same thing.

Since January 2022, Redcar and Cleveland Council has received the following 29 FOI requests from public authorities (26 from other councils and three from national quangos):

From one council to another Read More »