BBC bosses, my part in their downfall – part 1

It was twenty years ago today, at seven minutes past six in the morning to be precise, when the Today programme’s defence reporter Andrew Gilligan, mumbling and umming his way through a broadcast like he was still half asleep, said he’d been told that a government intelligence dossier had been ‘sexed up’ – thereby setting in motion a chain of events that led, via the shocking suicide of the biological weapons expert David Kelly, to an immense head-on clash between the Blair government and the BBC.

I was involved in these events. In 2003 I was normally a BBC radio producer, but for several months I was allocated to working with the top management on this fraught affair, as they wanted a journalist to help analyse and evaluate the conflicting claims and evidence.

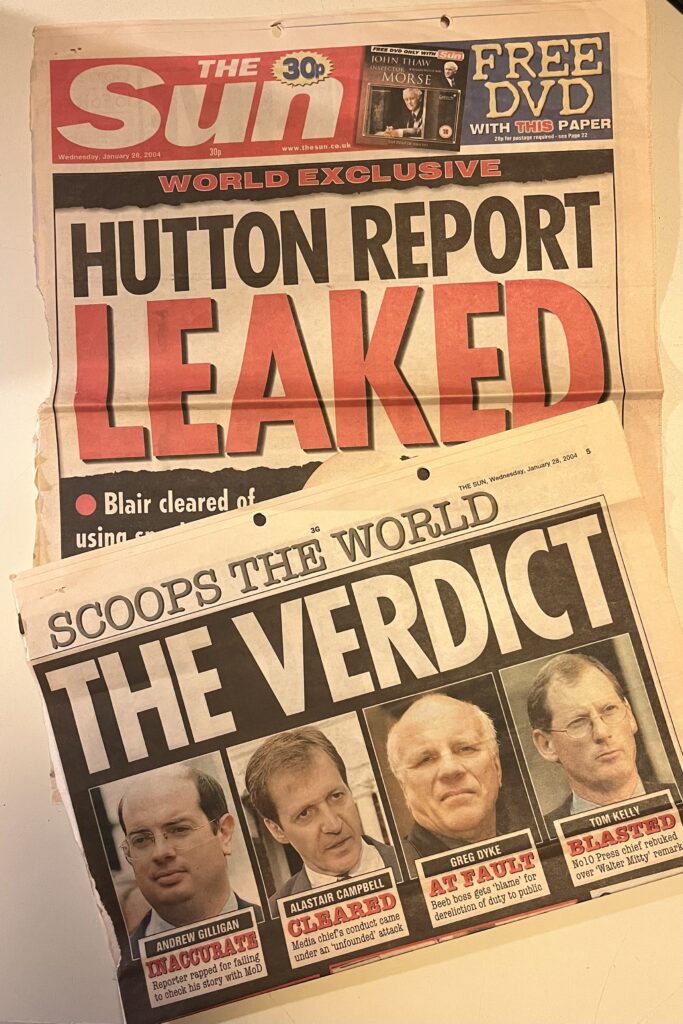

The dispute intensified uncomfortably and then after Kelly’s death became the subject of the Hutton Inquiry – the outcome of which was thoroughly disastrous for the BBC, requiring the rapid resignation of the corporation’s two leading figures.

A lot has been written about all of this. At one point my brain was crammed with every minor detail, every twist and turn, every argument and counter-argument, of the whole complex saga, and could have written a lot myself. But time has moved on.

Instead over the next few days or so I am going to post some broader recollections that still seem pertinent to me.

* * *

As with many other historical incidents, the outbreak of open conflict between BBC and government can be seen (according to your taste) either as a series of contingencies or as something almost inevitable that was waiting to happen.

The underlying fundamentals driving events were as follows. By May 2003 the situation in Iraq was deteriorating, in the wake of the initially successful US-led military campaign. Contrary to some pre-war intelligence briefings, no evidence that the Iraqis still had an active programme for weapons of mass destruction (WMD) had been found. The external and internal pressure on the government was mounting. And Downing Street (including Tony Blair personally) was getting increasingly stressed and irate over how the BBC was reporting matters. The BBC, however, was determined to stand up for its independence.

On the other hand there were many forks along the route where any of those involved could have chosen to travel another path. This includes the BBC.

One of the reports I wrote for internal use during this period identified 14 possible ‘turning points’ where the BBC management could reasonably have acted differently. But that was with the benefit of hindsight, and events took the course they did for understandable reasons.

* * *

In due course it turned out that there was much that was right in Andrew’s controversial reporting of this. But it wasn’t all correct.

His critics regarded him as a reporter who’d distorted the facts. I’d been a colleague of his previously when I was a producer on the Today programme on Radio 4. My experience of collaborating with him on stories was that he wanted and tried to get things right. In my direct dealings with him when we worked together he was conscientious and not cavalier about this.

But there were problems with the way he operated. Most of the time no one on the show seemed to know where he was or what he was up to, but periodically he would materialise in the office with what appeared to be a good story.

He was a maverick and an individualist. He didn’t like anyone else having oversight of what he was doing. Especially people he didn’t rate highly, and there were a lot of those. The result was that this made it difficult for other people to protect him – and the programme – from his mistakes.

Editors exist for a reason. Everyone makes mistakes. Reporters benefit when they regard and treat editors as a help, not as a hindrance.

In retrospect there was one story which seems ominously predictive of the way the Kelly coverage went. During the 2001 general election Andrew and I worked together on an investigation about possible postal vote fraud. I thought he did an impressively excellent job on it, and I was very happy with the scripted package that was broadcast.

But on the day it went out I was surprised to discover that he’d also done an early morning unscripted interview with the programme presenter (what was called a ‘two-way’ in our jargon). It transpired that in this he’d got confused and managed to get a central fact wrong. He hadn’t asked me in advance what he should say. Consequently his two-way and the programme’s reporting of the issue were ridiculed by people who knew about electoral law.

As far as I can recall now, I didn’t do anything about this. That was probably one of my mistakes.

* * *

More follows soon.

BBC bosses, my part in their downfall – part 1 Read More »