Will the left vote Tory?

What does a recent Scottish local government by-election tell us about the prospects for anti-Reform tactical voting?

Could anti-Reform ‘tactical voting’ block Nigel Farage from becoming prime minister?

Analysis of last month’s Caerphilly by-election for the Welsh Senedd suggests it was a significant factor in Plaid Cymru’s dramatic victory, with supporters of other left-wing parties voting for the Plaid candidate to ensure that Reform was defeated, as polls indicated only these two parties had a chance of winning.

And this month a YouGov poll covered in the Times reported that around half of LibDem and Green supporters would be willing to back Labour to stop Reform taking their constituency.

But to make a much bigger impact, left-wing voters would also have to be ready to vote for the Tories to keep Reform out – and the YouGov poll suggested that a significant minority would indeed do this: the net figures given were 30% of LibDems, 28% of Labour supporters, and 18% of Greens.

Discussion of tactical voting can be misleading. Most voters don’t really have a carefully ordered, fixed hierarchy of party preference in the way that some political punditry assumes. But the key point is that substantial numbers would appear more determined to block a party they really dislike rather than elect a party on which they are particularly keen.

According to the leading psephologist Peter Kellner, tactical voting along these lines in a general election could deny Reform 100 seats in England. Of these, 52 seats would instead go to the Tories, 44 to Labour, and 4 to the LibDems. A scenario like this would dramatically reduce Reform’s chance of winning an overall majority.

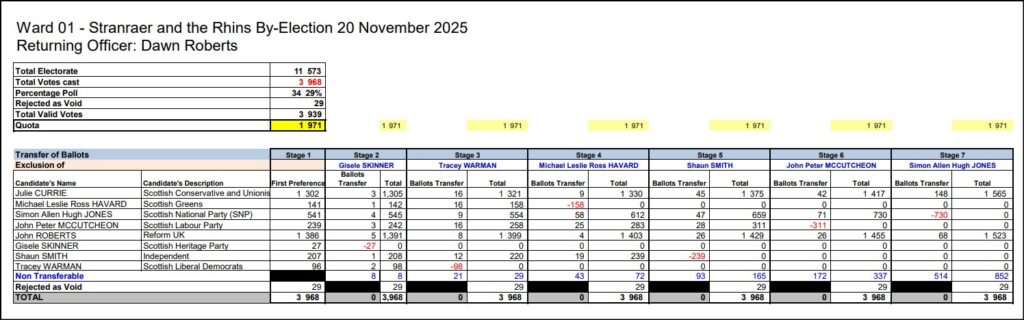

Given this background, it’s interesting to examine a by-election last week in a Scottish local government area, Stranraer and the Rhins. The ward is part of Dumfries and Galloway Council, and incidentally happens to contain Scotland’s most southerly point, the Mull of Galloway.

The conditions in this by-election turned out to constitute a kind of natural experiment about the extent of anti-Reform voting.

This is a location of traditional Conservative strength, and the by-election was narrowly won by the Tory candidate, just beating the new challenge from Reform.

It’s revealing because Scottish council elections are held under the single transferable vote (STV) system, where voters list candidates in order of preference.

At each stage of counting the votes, the candidate with the smallest number of preferences is eliminated, and the next preferences indicated by their voters are then allocated accordingly among the remaining candidates, before the next elimination.

This means we can gather information about the second or lower preferences of voters – and actual voters taking part in a real election, rather than respondents to a poll who are making predictions about how they might vote in hypothetical circumstances.

Whatever its merits as an electoral system, STV is certainly a boon for political analysts.

In this by-election the Reform candidate John Roberts was ahead at every stage of the count until the concluding one, when he was finally overtaken by the Conservative candidate, Julie Currie, who won by 42 votes, with 1565 to Reform’s 1523.

At the first stage Roberts had been leading with 1386 first preferences compared to Currie’s 1302. Then during the count Currie gradually caught up a bit at nearly every stage due to allocations of preferences as other candidates were eliminated, eventually nudging ahead to win thanks to the lower preferences passed on from the third-placed SNP candidate.

As the LibDem, Green, independent, Labour and SNP candidates were all knocked out, and lower preferences were transferred, the cumulative effect was that Currie obtained an additional 263 votes for the Tories, while Roberts only put on 137 more for Reform.

In other words 66% of these lower preferences transferred to the Conservatives and only 34% to Reform. This pattern was broadly consistent for each party eliminated during the count. And it was enough to ensure – narrowly and only at the last moment – that Reform lost and the Tories won.

This might seem to confirm the potential for such anti-Reform tactical voting for Conservative candidates by some on the left. But there are also some powerful pointers in the other direction.

Firstly it’s notable that about one in three of these voters actually preferred the Reform candidate to the Conservative, so the pattern of preference is far from universal. Nor is this at all surprising, given that Reform has been picking up support from across the political spectrum.

But perhaps more importantly, there were 852 supporters of these other candidates who in the end did not express any preference between Conservative and Reform. Thus overall, in what was clearly a two-horse race between the Tories and Reform, just 21% of the other voters preferred the Tories, and 11% Reform, so that the eventual net benefit to the Tories consisted of 10% of these others.

And this in a contest where due to the electoral system voters could still happily put their top preference first, while preserving the political impact of their lower preferences, without any need for the reluctant compromises of tactical voting.

This pattern is therefore significantly weaker than the picture which emerged from the YouGov poll. It could suggest that 10% is a reasonable upper limit for the proportion of left party supporters who might vote Tory to block Reform in seats where they are the two parties in contention.

On the other hand, 10% (or any figure close to it) is certainly not nothing. In a general election any degree of tactical voting by leftists for Tories to that sort of extent would be enough to affect some Tory versus Reform battleground seats and possibly the overall national position.

There are lots of caveats about all of this, naturally. While this was an actual election, it only consists of one local ward with about 4,000 voters taking part, in Scotland, under a different voting system, and could be completely unrepresentative. Not least, there may of course be all sorts of specific factors to do with the individual candidates and the local campaign, of which I am unaware.

And, in terms of the incentives to vote tactically, it must be said that even for many voters who are very uneasy about Reform, the prospect of a Reform candidate being elected to Dumfries and Galloway Council is not quite the same as the prospect of a Farage government.

Will the left vote Tory? Read More »