I’ve been analysing recently published data from the Electoral Commission about local campaign spending by candidates at last year’s general election.

Newly released figures on campaign spending at the last election confirm the suggestion that Labour sharply limited its electioneering efforts in seats which the Liberal Democrats might win from the Tories.

My analysis of Electoral Commission data shows that in potential LibDem target seats, Labour spent on average about £4,600 less than it did in other comparable constituencies.

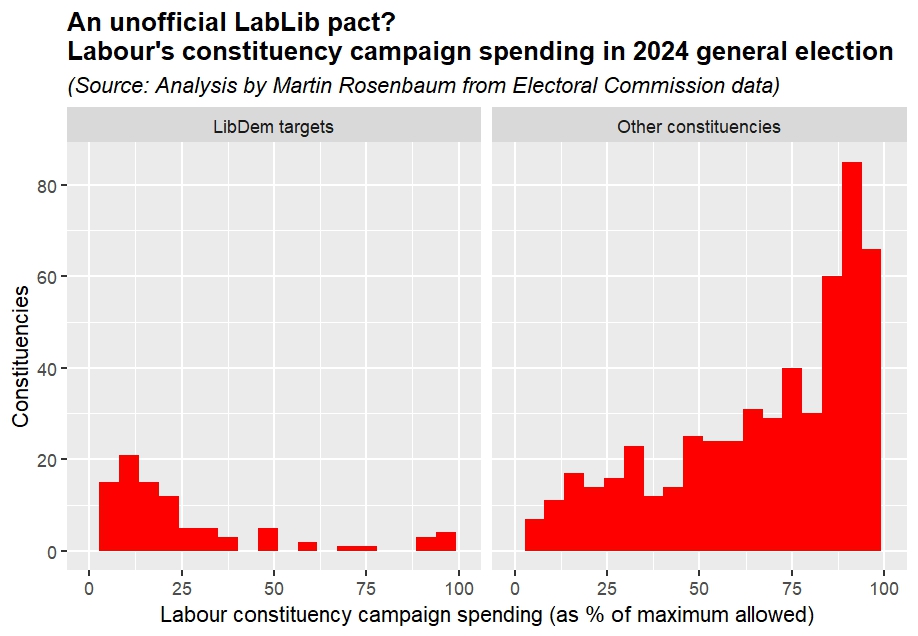

This chart demonstrates that in most places where the LibDems could be hopeful of victory, Labour generally spent a fairly small proportion of the maximum legally allowed for local campaigning at the 2024 election. This was in stark contrast to its general pattern of expenditure.

On average Labour candidates in these LibDem targets used only 26% of the legal limit, whereas Labour’s average in other seats was 68%.

While it could be argued that some of these seats were low Labour priorities as probably unwinnable, my statistical analysis shows that Labour put much less effort into campaigning in LibDem targets even after controlling for how well or badly Labour was positioned after the previous election in 2019.

Looking at seats then held by the Conservatives, and after taking account of the swing Labour would have needed to take the seat in 2024, Labour’s local campaign spending was £4,597 lower on average in these possible LibDem targets.

Party strategies

This fits with the claims made during the 2024 campaign that Labour was diverting its resources away from these seats, sometimes to the annoyance of disgruntled party activists.

In their local campaigning the LibDems concentrated resources very tightly indeed on their priority constituencies. Since these were predominantly ones held by the Conservatives who were clearly in massive electoral difficulties, they did not spend much money in other seats which were Labour or Conservative-Labour marginals.

These strategies suited both parties nationally who could each successfully focus their energies on maximising Tory losses and not competing against each other, without the need for any official agreement which would have been highly difficult and controversial.

I’ve defined LibDem targets here as constituencies where after 2019 they were the party in second place after the Conservatives (along with the much smaller number of places they held). This is a clear and reasonable demarcation.

However, it would not be identical to the list decided on by their party HQ, which added or dropped seats in line with fluctuating political circumstances and local factors. In any case this is more about which seats Labour would regard as sensible LibDem targets than the LibDems themselves. Nevertheless, even if there is a discrepancy of a few locations, that would not invalidate the very strong pattern this analysis identifies.

The local data published last month also reveals a very interesting contrast between Labour and Conservative spending patterns, which reflected the different political situations they faced when going in to the election.

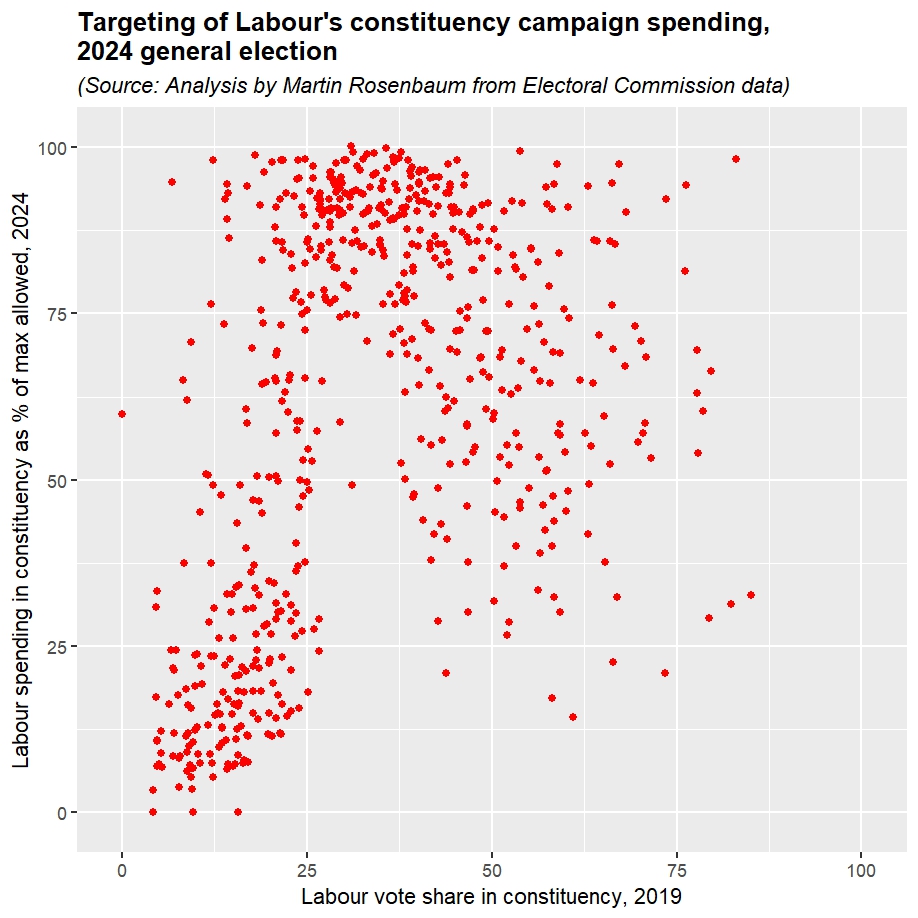

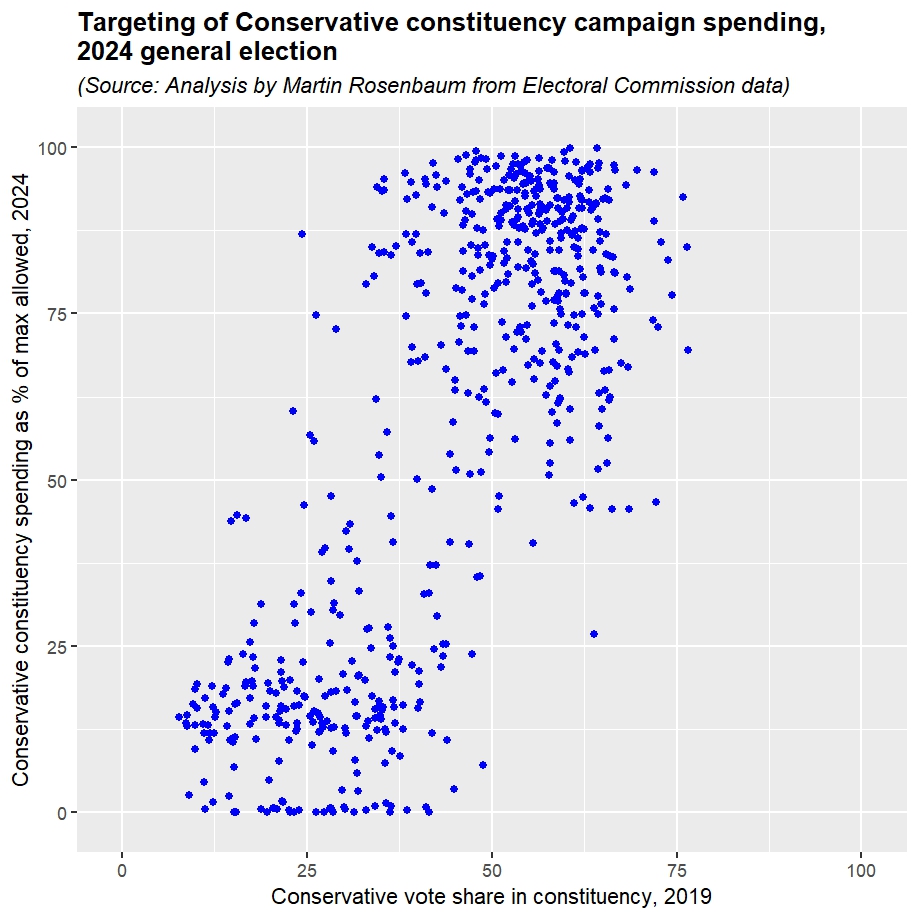

This is indicated in the next two charts, which compare the party’s spending in each constituency in 2024 to its strength there after the previous general election in 2019.

The ^ shape in the Labour graph shows the party tended to spend most in marginals, with significantly less expenditure in many hopeless seats and safe ones.

For the Conservatives, however, they had to concentrate resources on the seats they already held and were not able to assume any were safe. So their spending was much higher in places where they’d done better in 2019.

This expenditure refers to money parties use for electioneering in each constituency, including leaflets, posters, letters, meetings and office costs.

The legal limit in each place depends on the size of the electorate and whether the constituency is urban or rural. In 2024 the maximum allowed was generally in the range of £16,000 to £21,000.

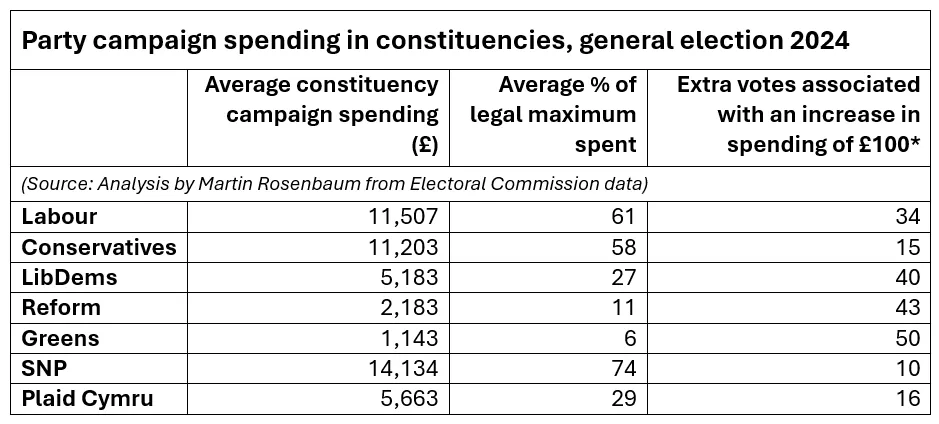

Overall Labour spent £7.2 million on local electioneering, while the Conservatives spent a little less, £7 million. For the LibDems the total was £3.2 million, for Reform £1.3 million, and for the Greens £700,000.

This is separate to money used for national campaigning. The legal cap on that in 2024 was £34 million for parties standing candidates throughout Great Britain. The Electoral Commission has not yet released the details of the national sums spent by the major parties.

There is some evidence that spending on constituency campaigning does matter. I analysed how many extra votes each party got for an extra £100 of local spending, after controlling for the party’s vote share in that constituency in the 2019 election.

The figures are given in the table below. However it is difficult to read much into this, as parties would also be devoting more effort to places where they felt things were going well, especially the LibDems, Greens and Reform. So the overall direction of causation is far from clear.

* This is the number of extra local votes in 2024 for that party associated with an increase of £100 in its local spending, after controlling for its votes in 2019 to take account of its position going into the election. (In the case of Reform, I used the figure for how the Brexit Party did in 2019, although they didn’t stand in many seats).