New disclosures from the National Archives reveal how ministers and officials struggled with the freedom of information system when it came into force in 2005.

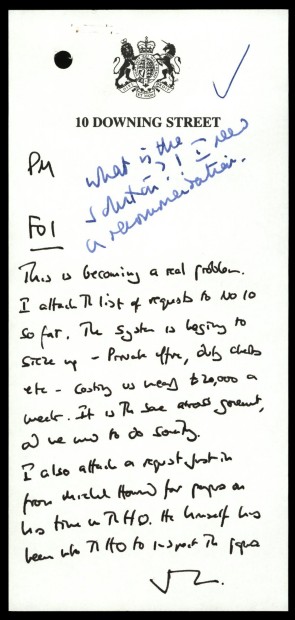

“This is becoming a real problem” – that’s what a top Downing Street adviser told prime minister Tony Blair about FOI, just a few weeks after the law to open up the state to more scrutiny had come into force at the start of 2005.

Government files just released by the National Archives shed new light on how ministers and officials in Blair’s administration coped with the new public right to make requests for government documents, with their reactions varying from compliance through unease to outright hostility.

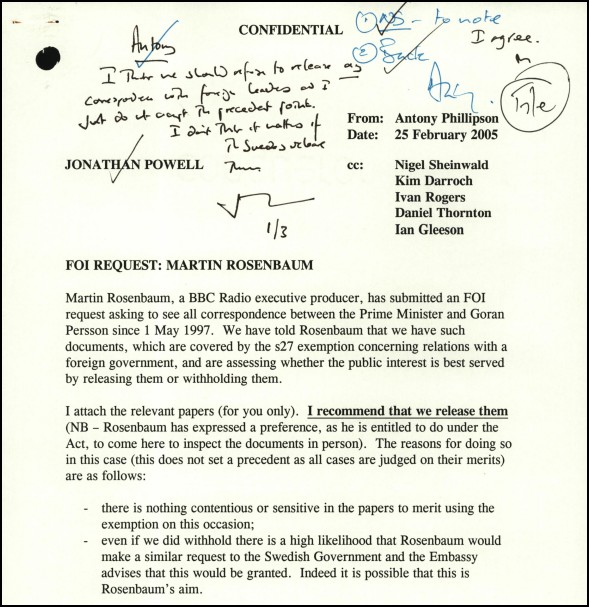

This particular memo was written in February 2005 by Jonathan Powell, who was then Blair’s chief of staff and today is still at the heart of power, as the current government’s national security adviser.

He told Blair: “The system is beginning to seize up – Private office, duty clerks etc – costing us nearly £20,000 a week. It is the same across government, and we need to do something.”

The prime minister replied: “What is the solution?! I need a recommendation”.

The government clearly found some of the initial rush of requests to be uncomfortable. In the following year they proposed new regulations to make it easier to reject FOI applications, but these plans met a lot of opposition and were abandoned.

Several years later, after he left office, Blair complained in his memoirs that civil servants had failed to warn him of ‘the full enormity of the blunder’ that in his view FOI proved to be. Powell also was later publicly critical of FOI, writing that ‘policymaking, like producing sausages, is not something that should be carried out in public’.

These files, which have been published under the 20 years rule for releasing old government records, also show how civil servants dealt with some of their first FOI cases.

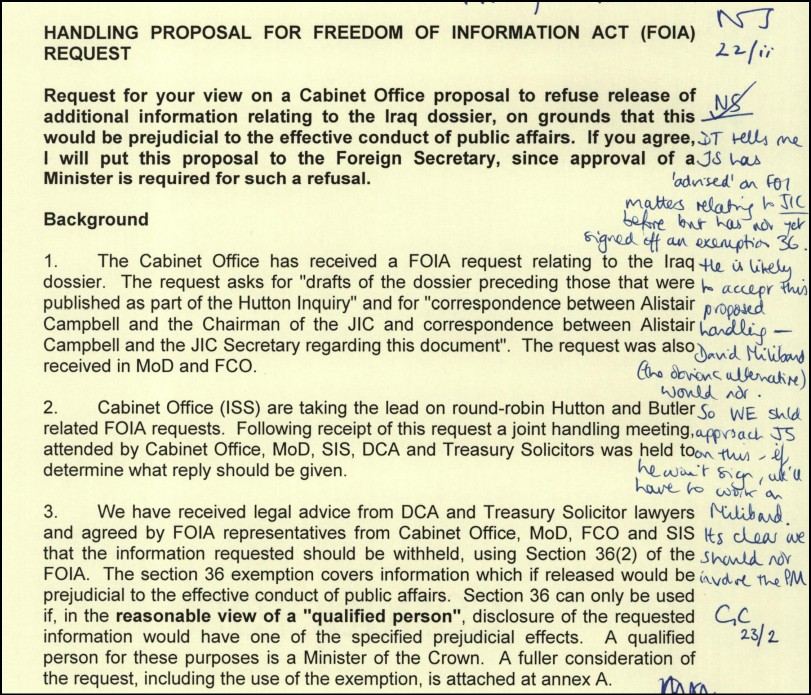

They reveal how officials who did not want to release certain material relating to the Iraq war discussed which minister to approach for sign-off. They decided to ask the Foreign Secretary Jack Straw as they expected he would agree with their planned refusal, as opposed to the Cabinet Office minister David Miliband who they thought would not go along with this. An official added that if Straw wouldn’t comply, ‘we’ll have to work on Miliband’. Straw did.

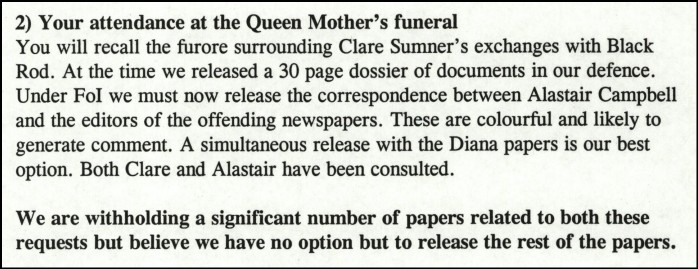

Other examples provide evidence of reluctant information releases which were enforced by the FOI law, as in this memo which an official sent to Blair.

I was particularly interested to find discussion of how to respond to one of my early FOI requests – for correspondence between Blair and the Swedish prime minister, Goran Persson. I’d already obtained some of this from the Swedish government, which had a greater culture of openness, and wanted to see what Downing Street would supply in comparison.

Blair’s private secretary for foreign affairs, Antony Phillipson, recommended giving me the material, which he said contained nothing contentious. But he seems to have been overruled by the chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, who was worried it would set a precedent. Powell wrote that he was opposed to releasing any correspondence with foreign leaders.

So this information has now finally been released by the UK government over 20 years after the Swedish government disclosed it.

It includes the letter Blair sent to Persson to say ‘thank you for Sven’. This was in the wake of the England football team beating Germany 5-1 in the World Cup qualifiers in 2001, an early triumph for the side’s new Swedish manager, Sven-Goran Eriksson.

I was once told by the then Information Commissioner Richard Thomas that Downing Street staff had informed him that they couldn’t send me this amusing but harmless brief handwritten note, which I had written about for the BBC after I obtained it in Sweden, as they hadn’t kept a copy of it. Yet funnily enough, here it is in their files.

The released documents also show that many ministers were particularly exercised about FOI requests for their diary information, such as who they had held meetings with.

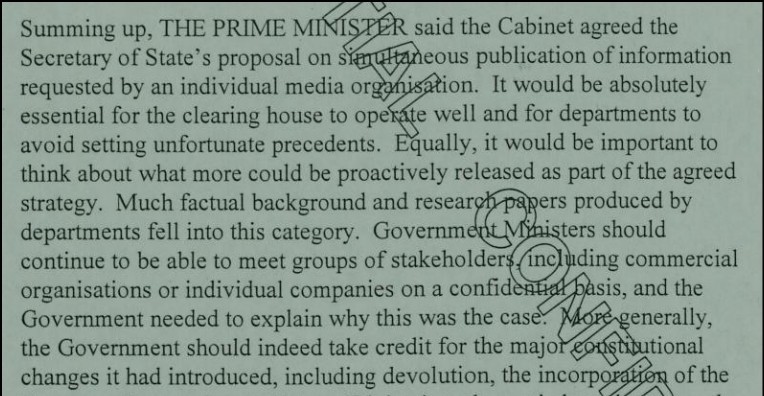

Policy on this was discussed extensively in correspondence between departments. The topic also featured prominently in cabinet meetings during the early months of FOI, as is disclosed in the 2005 cabinet minutes which have also just been released.

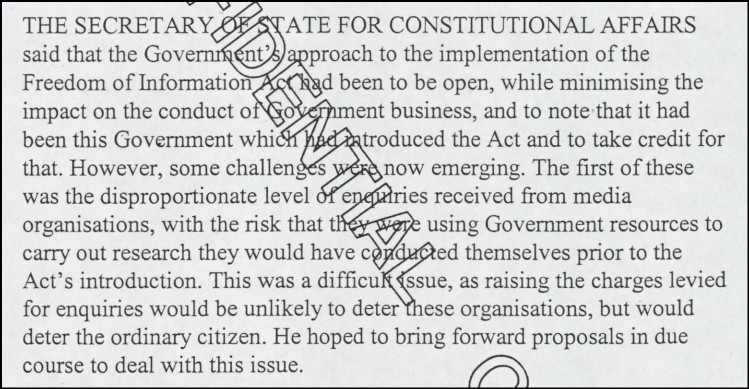

The cabinet minutes also give a broader view of how the new FOI system was regarded within ministerial circles, often with concern rather than pride.

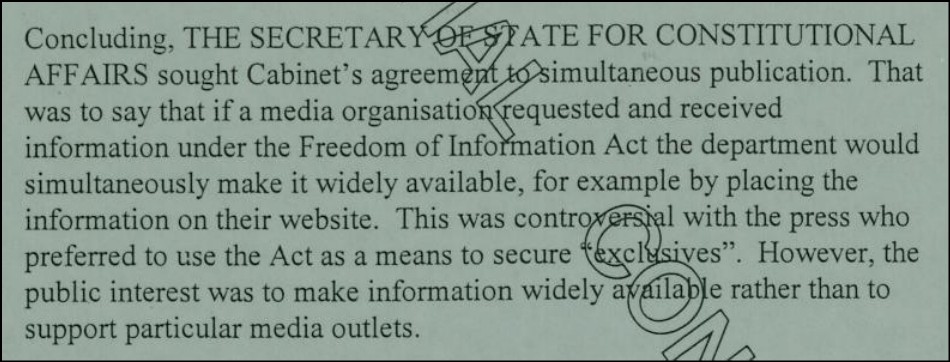

It is interesting to note that the cabinet minister responsible for FOI, the Constitutional Affairs Secretary Lord Falconer, was keen to get departments to publish FOI disclosures on their websites at the same time as giving the information to the requester. This was particularly in the case of the media.

Falconer did not appear to be happy generally with the media’s use of FOI, as he told the cabinet on another occasion.

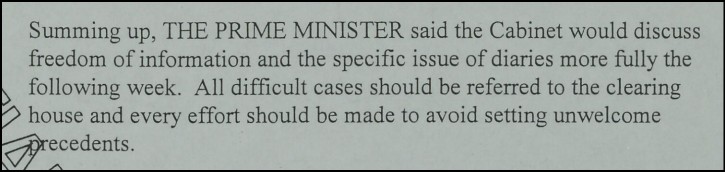

And finally, just before FOI came into force, this is how Tony Blair summarised matters to the cabinet, several years before he announced he was a ‘nincompoop’ for introducing the law.

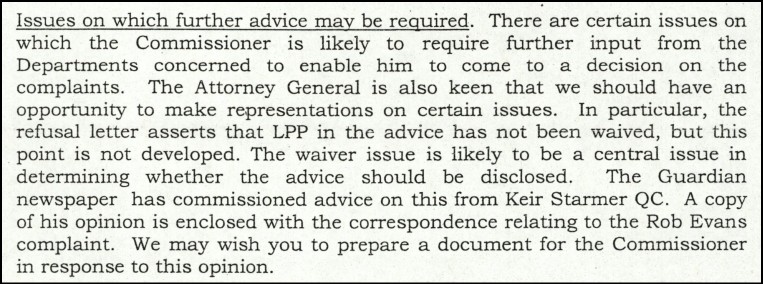

And one more thing. I wonder what Keir Starmer was saying back in 2005, in a legal opinion commissioned by the Guardian, on whether certain government legal advice should be disclosed.