Some headlines are meant to shock you, but they don’t always have the desired effect.

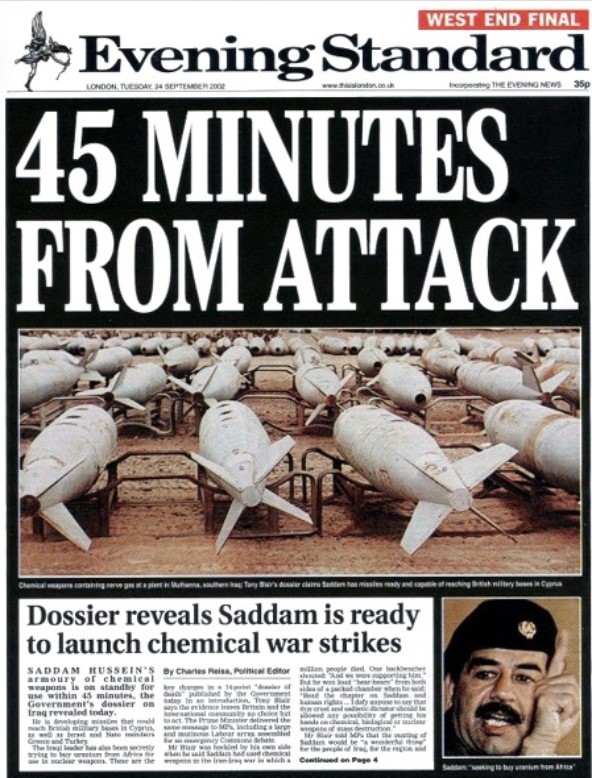

On the publication day in September 2002 for the Blair government’s key dossier on ‘Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction’ (as it was titled), I saw this on the front page of the London Evening Standard: ’45 MINUTES FROM ATTACK’.

And I remember thinking to myself, well, launching those weapons is actually rather slower than I expected.

At the time I clearly know nothing about WMD systems. But the government’s ‘intelligence’ on the matter, which should have been rather more accurate than me, also turned out to be hopelessly misinformed.

The so-called ‘45 minute claim’ was at the heart of the David Kelly controversy and the Hutton Inquiry. It came to symbolise the extent to which the published dossier had, or had not been, ‘sexed up’.

And in one of his broadcasts, the 6.07 two-way, Andrew Gilligan had said he’d been told by a senior official that it was included although ‘the government probably knew [it] was wrong’.

Broadly speaking, the claim was along the lines that Iraq could deploy some chemical or biological weapons within 45 minutes of a decision to do so. But in the Hutton Inquiry and surrounding discussion it was always referred to by the shorthand term of ‘the 45 minute claim’. And in fact it is hard to state exactly what the claim was, not least because it was phrased in four different ways in the dossier. Which might have been a clue to how bogus it was.

The dossier would have been more accurate if it had stated: ‘Some guy in Iraq apparently says that maybe Iraqi military units can fire a chemical weapon a few hundred yards or so on a battlefield within 45 minutes of an order, we don’t know whether he knows what he’s talking about’. But then that probably would not have produced the headlines convenient for the government, such as the Sun proclaiming ‘BRITS 45mins FROM DOOM’.

+ + +

So in retrospect how accurate and justified was the BBC’s reporting of David Kelly’s unease about the WMD dossier?

My view in summary:

1. The reporting by Andrew Gilligan and the BBC generally contained a substantial element of truth, about the process of compiling the WMD dossier leading to overstatement of what appeared to be the evidence.

2. But in parts the reporting was confused and inaccurate.

3. The key exaggerated statement which the BBC headlined repeatedly (and was much more significant than anything Andrew half-mumbled at 6.07am that went unnoticed for weeks) was that the BBC had been told that Downing Street included the 45 minute claim in the dossier against the wishes of the intelligence services.

4. The accurate alternative to this that we should have attributed to the source was: ‘The 45 minute claim was included in the dossier against the wishes of some experts from defence intelligence, who thought Downing St was responsible for doing so’. This would have been true, important and definitely worth reporting.

This is my personal opinion, arising from the months I spent working through and analysing every angle on the whole story to help inform the BBC management’s case. It was not a position adopted by the BBC.

It is also simply an overview, leaving aside all sorts of detailed arguments about the contents of the government dossier and the process for compiling it, the phraseology of individual reports, some less important errors made by some BBC programmes, etc. But this piece is easily long enough anyway without me going into more of that.

+ + +

So does that mean the Blair government ‘lied’?

There’s an occasional but continuing ritual, an exchange of allegation and denial over this, in which Blair, Campbell and others are accused of lying, and they respond in a rather pained manner to insist that it’s fine, of course, to condemn the war, but please don’t say they acted in bad faith, as they really did think Iraq had the WMD.

In my view this starkly dichotomous dispute completely misses the main point. I’m sure Tony Blair genuinely believed that the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had access to WMD, and also that he was genuinely very worried about it. Most people thought Iraq was likely to have an active WMD programme. Saddam had deployed such weapons in the past, and continued to act much as if he still had use of them – not unlike a household which keeps prominently displaying a ‘beware of the dog’ sign, because it’s useful to intimidate the neighbours, even after the dog is no longer around.

In holding these views Blair was a victim of groupthink and a failure to question assumptions, but in terms of how he presented things to the public, his real fault was the unjustified way in which he exaggerated the strength of the intelligence.

He told the House of Commons that the intelligence picture was ‘extensive, detailed and authoritative’. In reality, it was very limited, patchy, superficial and poorly sourced. Given this reality, it’s not so surprising that it also turned out to be completely wrong.

+ + +

There were about 20 people on the BBC side who were given access to the Hutton Report 24 hours before publication. I was one of them.

We were divided into small groups in rooms in Broadcasting House, with numbered copies. Given it contained 740 A4 pages it might have seemed a bit daunting to go through it, but over 90% of it consisted simply of lengthy extracts copied-and-pasted from evidence and documents, and one of the BBC lawyers directed us immediately to the few important pages.

We’d prepared all sorts of lines to take to defend the BBC, but it rapidly became apparent that they weren’t really up to the scale of criticism the corporation received from Lord Hutton.

From the government point of view the Hutton Report was so good, it was bad. Hutton’s verdict was so one-sided that it lacked authority.

From the BBC point of view I vaguely hoped that the report was so bad, it might somehow be good. But that didn’t transpire. It was just unredeemably bad.

In my view it was also a shoddy, poorly argued, inadequate exercise. There were valid criticisms to be made of the BBC, as I’ve indicated here, but Hutton didn’t grasp the issues properly and made completely the wrong ones.

The Hutton Report was full of flaws. There’s no point now in going through them all. Many have been thoroughly detailed, for example, in Greg Dyke’s memoirs and in the book by Kevin Marsh, who edited the Today programme at the time of Andrew Gilligan’s broadcast.

To take just one, which struck me immediately as blatant, Hutton said that the allegation the dossier was ‘sexed up’ was ‘unfounded’, on the grounds that the audience would take this to mean that it was ’embellished with false or unreliable items’. He had no basis for this only choosing this interpretation. He was acting like a judge who has to decide on a specific meaning for a word in legislation. In fact, ‘sexed up’ is a very ambiguous term which certainly can cover much weaker assertions. For that reason it’s probably not a phrase conducive to clarity of analysis, but it’s entirely defensible as accurate in this context.

Hutton also made ill-founded criticisms of the BBC’s editorial structures and processes, which he clearly didn’t understand. To be honest these can seem obscure at times, even to those of us working there. But Lord Hutton was the one person who’s ever been given the opportunity to call witnesses and ask them questions until he had worked it out, which he failed to do.

+ + +

That might seem like a BBC perspective on matters, but a few years after the Hutton Report came out, I sat down at dinner opposite a leading member of the government’s legal team at the inquiry. And his view wasn’t really all that different from mine.

He told me that the Hutton Report was an ‘intellectually weak’ piece of work, an assessment with which I entirely agree. He also said the following:

- Hutton was a ‘second-rate judge’ and ‘not up to the same standard as other Law Lords’

- His report ‘summarises both sides and says “I come down on this side” without reason or argument’

- He was ‘the kind of judge who sees everything in black-and-white, either all for you or all against you’

- He ‘ignored criticisms of the government, but his report would have carried more credibility if he had included them’

- Alastair Campbell ‘went over the top and should have been criticised too’

As a verdict on the Hutton Report, I think all this is true.

+ + +

POSTSCRIPT

At that time one of the boxes you had to fill out on your annual appraisal form in the BBC was to state if there were important things that could have gone better with your work during the year. So on my form I jokingly put ‘Yes, avoiding the resignation of the Director General and the Chair of the Governors’.

I have to confess that we journalists did not always take to HR initiatives like the ever-changing appraisal system with the level of seriousness and commitment that the HR people felt they merited.

A year or so later I bumped into Greg Dyke in the crowd at a Brentford game at Griffin Park. He seemed in a cheerful mood (maybe Brentford had won, I don’t remember) and we chatted amiably. However I then told him what I’d written on my appraisal, and despite his surface good humour, I don’t think he found it at all funny. I regretted it. So if you’re reading this, Greg, I apologise.

There were three big and fundamental problems with Gilligan’s report, which his defenders (especially Kevin Marsh) overlook. The first was his use of the term “government”: “the government probably erm, knew that that forty five minute figure was wrong, even before it decided to put it in”. Most people would understand “the government” to mean the political element – Ministers or special advisers. The Hutton Inquiry proved that the concerns were within the civil service and never reached Ministers or special advisers. Had Gilligan reported that some civil servants thought it was wrong but were overruled by more senior civil servants, he’d have had a correct but much less sexy story.

The second problem is that Gilligan accepted Kelly’s naming of Alistair Campbell as personally responsible for dismissing doubts about the claim, as key evidence rather than Kelly’s pure speculation. The evidence of Susan Watts’ subsequent phone call shows Kelly evidently suspected Campbell but had no direct knowledge. In fact Kelly was even wrong to identify the 10 Downing Street press office.

The third and fundamental problem is that Gilligan never checked whether Kelly was in a position to know. Kelly’s contribution to the dossier was to factcheck one section. He was not on the Joint Intelligence Committee; he fed his knowledge into it. Further investigation of the process of compiling the dossier might have brought that to light, and would also have established that under BBC producer guidelines the whole story was insufficiently sourced to be broadcast.

When Alistair Campbell demanded a retraction and apology, he was owed one because he had been wronged.

For what it’s worth I’d say the Hutton report is the worst written inquiry report I have seen. It is far too heavy on quoting material and very light on explaining how Hutton came to his conclusions. However Hutton was right about almost all of them.

Thanks for some interesting points, David.

On your first point, I think there is indeed an issue about the word ‘government’ but that sentence was wrong for other reasons too. However it’s important to note that the civil servants who were overruled actually included leading specialist experts in the subject in defence intelligence. They knew their stuff. That’s a significant story.

On the second point, there is some validity in what you say, but Andrew’s crucial reference to Campbell’s alleged role was only in his Mail on Sunday article, not on the BBC – and the BBC management did not feel editorially responsible for that. At that time BBC staff had more freedom to write for newspapers than was later the case. I’m sure it infuriated Campbell, but he turned all his anger on the BBC, not on the Mail on Sunday.

Your third point raises a significant issue as to Kelly’s importance, which I could have written about. When his name first emerged, I’m pretty sure no one in BBC management had any idea who he was. One of my tasks was to find out. From talking to several leading figures in the field it became clear he was obviously a highly respected expert. But if did you an internet search at that very point in time, the top result implied at first glance that he was the MoD’s chief scientific adviser (in fact, he was chief scientific adviser to just the MoD’s Proliferation and Arms Control department). I think that led some in BBC management to initially form an exaggerated idea of his importance and his likely role in the dossier.