The new UK Information Commissioner, John Edwards, takes office today, after recently flying across the globe from New Zealand where he was Privacy Commissioner – and, as he reported on Twitter, encountering on arrival a kindly stranger at Gatwick airport who gave him a pound coin to unlock a luggage trolley.

However the UK’s FOI community are not convinced that Edwards himself will turn out to be a kindly stranger. Indeed his arrival in the post is regarded with some trepidation.

This is primarily because of the surprising and indeed disconcerting remarks which Edwards made in September to the House of Commons DCMS committee, at his pre-appointment hearing.

In the FOI section he quickly and without prompting raised the topic of what he called the “extraordinary administrative burden” arising from some FOI requests, and added that “it is legitimate to ask a requester to meet the cost of some of that administration, otherwise you see there is a potential for cross-subsidisation of people who are overusing or even abusing those rights”.

Edwards also expressed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for expanding freedom of information further for private sector bodies who are contracted to deliver public services – “I suppose extending FOI to cover those organisations would be one option”, he replied rather guardedly to this suggestion from an MP.

These statements are a contrast to the stronger pro-transparency stances adopted by previous UK Information Commissioners, who have opposed fees for freedom of information requests, defended FOI against rhetoric about “burden” and “abuse”, and advocated such a broadening of the FOI system.

Nevertheless, for those who like a more positive take, there is a more optimistic viewpoint. This is that Edwards was effectively talking about the situation in New Zealand rather than the UK.

From his remarks he seemed unaware of the tight legal cost limits that apply to FOI responses in the UK. These curtail the administrative effort and cap costs, and also push requesters (or at least the more effective ones) into making narrower rather than wide-ranging applications. Such specific limits do not exist in New Zealand, where the law instead does allow charging for some FOI requests but for a range of reasons public bodies often do not make requesters pay.

Possibly Edwards had briefed himself inadequately on the FOI part of his new role. But that could also turn out to be a problem, if it is symptomatic of a neglect of FOI.

This has already been a serious issue at the UK Information Commissioner’s Office, whose resources, public statements and high profile casework in recent years have increasingly been dominated by the data protection side of their responsibilities, to the detriment of their FOI work.

And in New Zealand as Privacy Commissioner for eight years, Edwards himself was focused on the data protection and privacy field. The country’s freedom of information system is enforced by a different regulator, the Ombudsman (Edwards worked there much earlier in his career).

However, there are some positive views on government transparency in the personal blog Edwards wrote when a lawyer in private practice, before becoming Privacy Commissioner.

In one 2011 piece he argued for the disclosure of free and frank policy advice as “precisely what the electorate needs”. In 2012 he praised the release of briefings for incoming ministers, even if this meant they were then written with a view to public consumption, on the basis that “officials should prepare advice that to the greatest extent possible can stand up to public scrutiny”.

The disclosure of internal government policy advice and especially cabinet papers, particularly once decisions have been taken, has gone much further in New Zealand than under FOI in the UK (although journalists there are still not happy about what they don’t get). If it turned out that Edwards actually wanted to import some of that culture and practice from back home into the UK FOI system it could have a big effect on the role of the ICO.

(Incidentally, his blog also reveals that the Gatwick luggage trolley incident was not the first time he was saved financially by a helpful representative of Britain. As a young budget traveller he once faced a tricky situation with some Bolivian officials who demanded an extortionate sum to stamp his passport. Fortunately he was rescued by the intervention of the British Consul and her insistence on “bureaucratic banalities” – she maintained that any such payment would need a receipt, which for some reason the law enforcers of La Paz were reluctant to provide. And whether for good or ill, Edwards is now about to encounter more of the bureaucratic banalities of the British state).

Ensuring that freedom of information does get enough attention from his office and is pursued with energy and commitment is one crucial challenge facing the new Commissioner. Another is rectifying the sorry state of how the ICO itself complies with FOI law.

The Privacy Commissioner’s office in NZ is subject to the information rights regime of the country’s Official Information Act (OIA). In the four-year period of 2017-21 it received 130 information requests, of which only one was answered outside the legal timeframe. And the Ombudsman’s office tells me that during Edwards’ tenure as Privacy Commissioner it did not uphold a single OIA complaint against the PC.

If Edwards can grasp the issue here with determination and replicate something like that sort of performance at the ICO it would indeed be a major achievement, but the ICO is a much bigger and more complex organisation with a much larger casework, and a very poor track record recently on handling its own FOI requests, which often gives the ICO the embarrassing task of rebuking itself.

In his valedictory office webinar in New Zealand, Edwards cautiously stressed the “constant tension” and “balance” between assisting organisations to achieve their objectives and being an assertive regulator and enforcer. That was in the context of data protection, but in the FOI area as well his impact will depend on which side of that balance he actually gives most weight to.

It will also rest on what is now his personal balance between seeing the world through the perspective of administratively minded state officials or that of a lawyer representing the individual rights of citizens.

One of his New Zealand habits that it looks like Edwards will maintain is his personal Twitter feed. Informal, folksy, casual and sometimes glib, its tone and content will be rather unusual for a top-ranking British public figure at a state regulatory body.

He has combined serious points on privacy policy and some later deleted stinging criticism of Facebook (“morally bankrupt pathological liars”), with comments on the latest cinematic releases, lots of jokey remarks and funny videos, and an occasional willingness to get involved in political controversy.

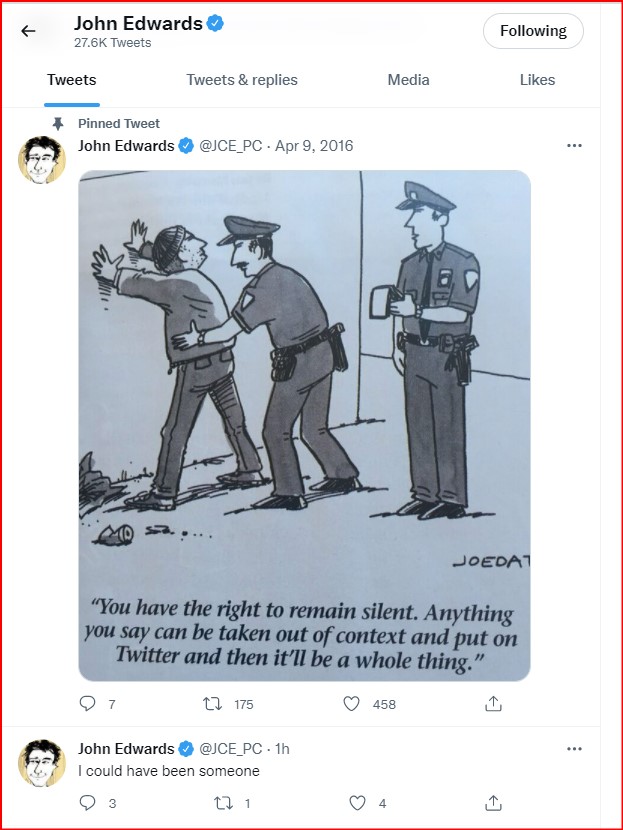

It sometimes caused him trouble in New Zealand, and unless he’s very careful I predict it will cause him more trouble here (in many ways I think that’s a shame, as I like his friendly informality, but that’s how things work), despite the proclamation in his pinned tweet below:

His recent “I could have been someone” tweet also captured above was presumably a Christmas reference to the lyrics of Fairytale of New York. Whatever deeper personal meaning may lie hidden in his gnomic expression we can only guess at. Still, if you meet him your opening conversational gambit could be “Well, so could anyone” (perhaps after you’ve offered him a pound coin).

What kind of “someone” will he turn out to be as UK Information Commissioner?

Somebody in New Zealand who has observed Edwards’ work closely over many years told me: “He genuinely cares about people’s well-being and that institutions are well governed”.

If Edwards wants to deliver on these two notions in the freedom of information field here, he needs to ensure (a) that people’s individual rights to access public sector information are enforced rigorously and assertively, defended against resistance and backlash, and ideally extended; and (b) that the ICO itself becomes a prompt and efficient and well-governed institution in handling information casework and requests.

We shall see. Meanwhile I find it difficult to imagine any of his predecessors as Information Commissioner so gleefully tweeting this video.

Update

John Edwards has responded to my blog above with the following comments on Twitter:

“I think any trepidation of the sort you mention, based as it is on a single off the cuff response at select committee, informed, as you say, by my NZ experience, is misplaced. I have always been a strong advocate for FOI, and will continue be in my new role.”

“Also, what you have characterised as “a distinct lack of enthusiasm for expanding freedom of information further for private sector” was more in the nature of a thoughtful pause to consider the various different ways that could be achieved.”

He also said: “I didn’t even know those old blog posts were still accessible!”