What will be the political impact of the additional challenges that MRP polls may face at the next general election?

Last week’s local election results suggest that we are entering a new phase of multi-party politics across Britain.

Setting aside the local and national policy consequences, the impact will also be to make our elections harder to forecast and to complicate the task of the polling companies.

Yesterday I attended a meeting organised by the British Polling Council to discuss ways of tackling the industry’s failings at the last general election, when the polls significantly over-predicted how well Labour would do.

The next general election is likely to present further difficult challenges for the pollsters, particularly for MRP polls which proliferated in 2024. I think this could have important political ramifications.

The MRPs apply statistical modelling to survey data in order to produce individual constituency forecasts based on the local demography, and thus predict how many seats each party will win. Despite the headline on this piece, it stands for Multilevel Regression and Post-stratification, rather than Maybe Right, Perhaps.

Last year the MRPs made a positive contribution to understanding the pattern of public opinion by correctly showing that Labour and the LibDems would benefit from different swings in different seats, rather than the traditional norm of roughly uniform swing across the country. They were therefore a very useful expansion of polling techniques.

However the MRP polls all exaggerated the level of Labour success, as I have previously analysed. This systematic error across the industry stemmed largely from the voting intention polling figures which were fed into the statistical models.

If, as seems probable, the current electoral fragmentation continues until the next general election, then predicting constituency winners will surely get harder, for the following reasons.

- There will be many more seats where more than two parties have a realistic chance of coming top.

- Winning margins will be narrower.

- Pollsters will have to try to identify demographic characteristics of voters across a greater range of political attitudes.

All this will make forecasts more sensitive to problems with unrepresentative survey samples and any flawed assumptions or procedures in the statistical modelling. It is also likely to produce greater differences in constituency predictions between the various pollsters.

We already saw in 2024 how the MRPs can profoundly affect a campaign. Their forecasts for each seat were relied on by a number of tactical voting websites, and in local electioneering political parties made great use of those estimates which were convenient. The MRPs also probably had a substantial impact on the morale of some party activists, both positively and negatively.

All these points were made at the BPC event yesterday. For example, Martin Baxter from Electoral Calculus described how he received irate complaints about some local parties quoting out-of-date seat analyses in their election literature, but despite his efforts there was nothing practically he could do to stop them.

I expect next time there will be greater variation and inconsistency, with more opportunities for parties to cherry pick and publicise forecasts that suit them. We’ll also see more instances of different tactical voting organisations issuing contradictory advice. Sounds like a recipe for chaos and confusion. And perhaps more calls for polling to be banned during campaigns.

However I should note that one factor will help the MRP statistical modellers at the next election. As Prof Chris Hanretty pointed out yesterday, they won’t have to cope with the complication of new constituency boundaries.

As well as these challenges, the MRPs will also face the fundamental issue that the political polling industry in general does – the accuracy or otherwise of voting intention data.

The major problematic factors in 2024 considered by the BPC’s member companies, as I have reviewed in the past, were late swing, ‘shy Tories’, difficulties with reaching over 75s and the less politically engaged, and religion/ethnicity.

No one knows of course whether next time there will be much late changing of mind by the electorate. Some of the other concerns may be dealt with by more sophisticated demographic modelling and more ingenious or determined ways to survey the kind of voters who aren’t enthusiastic about being polled. But the problem of ‘shy Tories’ may get trickier to handle.

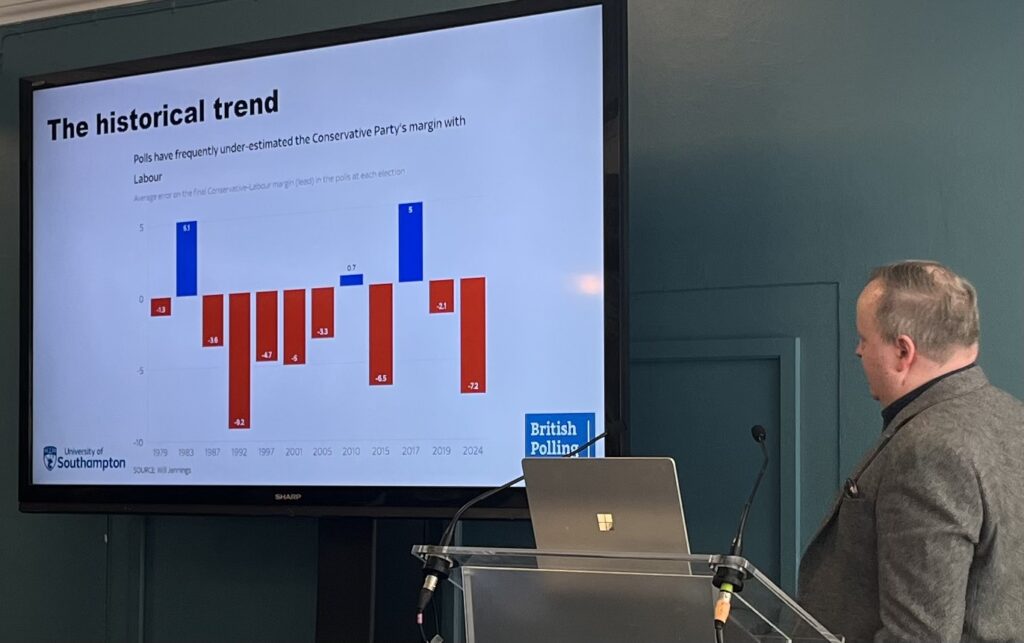

Pollsters historically and internationally have faced a frequent (but not universal) difficulty of under-stating backing for right wing parties (as can be seen in this chart presented by Prof Will Jennings). In the UK most pollsters try to manage this by weighting samples according to how people voted in the past.

Yet at a time of increasing volatility in the electorate, with chunks of public opinion churning around in all sorts of different directions, this is becoming much more awkward than in an era predominantly of neat two-party uniform swing.

This may also leave pollsters with dilemmas, as was illustrated at the meeting by Robert Struthers of BMG Research. Given how age was very strongly associated with voting patterns in 2024, it would surely make sense to take account of mortality and adjust for Tory voters (who tended to be much older) being more likely to die between then and the next election. But if you are already worried that your polling is under-stating Tory support, this would only take you further in the wrong direction.

Prof Patrick Sturgis also raised what could become a growing problem in the world of online survey research, which is that of questionnaires being completed by bots or organised bogus respondents, so that financial or other incentives can be claimed. This could be exacerbated if the fakers increasingly purport to be the hard-to-reach groups that pollsters may be upweighting in analysing samples.

It’s expected that the presentations (which I thought were impressively interesting and candid) given by the polling companies at yesterday’s meeting will be placed on the BPC website, to add to the analyses which are already there. Well done to the BPC, which aims to increase transparency in the UK’s political polling industry, for arranging the event.

The pollsters are continuing to grapple with all these issues. In particular they are awaiting the release of delayed data from the large-scale academic British Election Study, which may shed further light on what went wrong for the industry in 2024.