The general election result last July was certainly a ‘Labour landslide’, but it wasn’t the even bigger, ginormous landslide which the polls predominantly predicted.

We were saved from the normal cliched headline ‘Polls Apart’, because the polls were all together on one side of reality, overstating Labour and understating the Tories.

I’ve been examining the reasons provided by those polling companies who have publicly tried to explain how these forecasts went wrong. They focus on the following factors: late swing, religion, turnout, ‘shy Tories’, and age.

The most recent company to publish its analysis was YouGov, which did so just before Christmas, also announcing that it would adopt a new methodology from January.

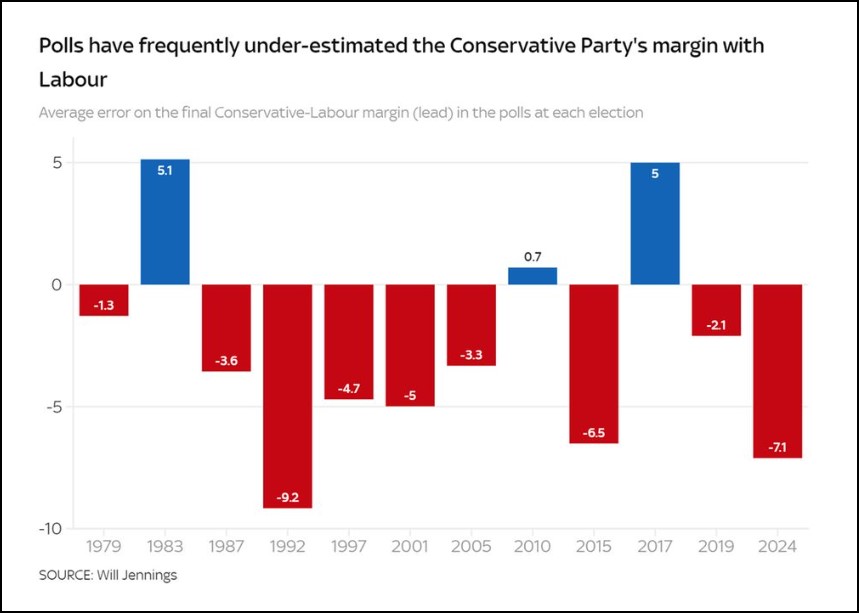

The election polls significantly overestimated Labour and underestimated the Conservatives, as shown in a chart from Will Jennings.

While this pattern has often happened, in terms of the difference between the two parties, this was their biggest miss since 1992, exaggerating the gap on average by 7 percentage points.

The constituency prediction models known as MRP polls were also all awry in the Labour direction, as demonstrated in the dataset collated by Peter Inglesby.

Of course some polls were much nearer to the actual outcome than others, as the companies that did reasonably well and got closest are naturally keen to stress, and as I myself have analysed in the past. But the industry as a whole clearly systematically over-predicted Labour, and that’s not good for the world of opinion research.

This is despite the fact that one can argue this was a tricky election to get right, with an increasingly volatile electorate, a very large swing, an important new party, the impact of independents, and changes in how demographic characteristics such as education and class link to voting behaviour.

If the result had been close, the level of polling error involved would have created a sense of chaos and surely have become a crisis for the industry. However the problem has been disguised by the fact that the only point at issue was the extent of the landslide, and so it did not disturb the central narrative of the election.

Pollsters are constantly seeking to improve their methods, and indeed the MRP models last July were a positive contribution to getting the overall impact correct, confirming the value of innovation. Companies have been reviewing their performance and what went wrong.

The British Polling Council (BPC) is collating relevant research from its members on its website. So far work from six organisations has been added. As well as YouGov, the others are BMG, Electoral Calculus, Find Out Now, More in Common, and Verian. It’s possible that more BPC members will add further submissions in due course.

I’ve been reading them to see what prevailing points emerge on an industry-wide basis.

It is important to note that given the companies have different methodologies, this implies there could also be variations in what each got wrong. But the fact that they were all out in the same pro-Labour/anti-Tory direction suggests that as well as any individual aspects there is also something significant which is shared.

Although there is no unanimity, their findings do reveal some common themes. (None of them discuss the issue of ‘herding’, the claim that error can be exacerbated if some companies sometimes take decisions in such a way that they stay in line with the crowd – a charge which is very unpopular within the industry).

Late swing

Three companies – BMG, More in Common and YouGov – attribute the error partly to ‘late swing’, due to people changing their mind about how to vote at the last minute after final opinion surveying ended. A cynic might say that this is the most convenient excuse for the industry, as it is the least challenging to the accuracy of their methods. Maybe, but the fact that it is convenient doesn’t necessarily mean that it is wrong.

Beyond the data presented, I have to say I also find this plausible based on anecdotal evidence, with the forecasts of a huge Labour victory nudging some intending supporters into eventually switching to vote for someone else, such as the Greens. In this sense the polls ironically could have been their own enemies, almost a kind of partially self-negating prophecy.

However Electoral Calculus finds no evidence of late swing, and in any case none of the companies thinks it can approach the full explanation, which still leaves a methodological challenge for the industry.

Religion/ethnicity

The pollsters seem to have failed to reflect the increasing fragmentation of the ethnic minority electorate, with some Muslim/Pakistani & Bangladeshi voters abandoning Labour, often for independent candidates who campaigned about the situation in Gaza, while Hindu/Indian voters drifted towards the Tories. This factor is referred to by BMG, More in Common and YouGov. It is clear that election analysis can no longer crudely treat voters of Asian heritage (let alone all ethnic minorities) as if they are one political bloc.

More in Common suggests that Muslims who currently take part in online market research panels are probably not representative of the overall Muslim population, being more likely to be second or third generation immigrants, and less likely to be born outside the UK or not speak English. The company says it will probably modify its weighting scheme.

Similarly YouGov says it will incorporate a more detailed ethnicity breakdown into its modelling in future.

However, the numbers of voters involved, while crucial in certain seats, mean that this could also only be a very partial factor nationally.

Turnout

Taking account of likelihood-to-vote is a notoriously difficult problem for pollsters, who employ a range of strategies to estimate how many of each party’s proclaimed supporters will actually go to the trouble of casting a ballot. Three companies – BMG, Electoral Calculus and YouGov – include the overpredicting of Labour voters’ turnout as a factor in the 2024 error.

YouGov argues the cause stemmed from panels which over-represented people who would actually vote, especially for low turnout demographic groups. The company says that from now on it will base turnout modelling purely on demographic data, rather than respondents’ self-reported likelihood-to-vote.

This sort of problem has been a general industry issue in the past, of over-sampling the more politically engaged (who tend to be keener to take part in this kind of survey).

However it is awkward for pollsters to get turnout adjustments correct. There is no guarantee that what worked best last time will be best next time, as the commitment of different groups to implement their asserted voting intentions may depend on the political circumstances of the moment. Ironically again, the forecast Labour triumph last July might have pushed some of the party’s less determined supporters into not bothering to go to the polling station on the big day.

Shy Tories

This has also been a traditional difficulty for the polling industry, where those of a Conservative outlook are somewhat less willing to express their allegiance – possibly because they feel in some sense disapproved of or intimidated (this is sometimes called ‘social desirability bias’), or perhaps alienated from polls. Again, the extent to which it happens can also depend on the political atmosphere of the time.

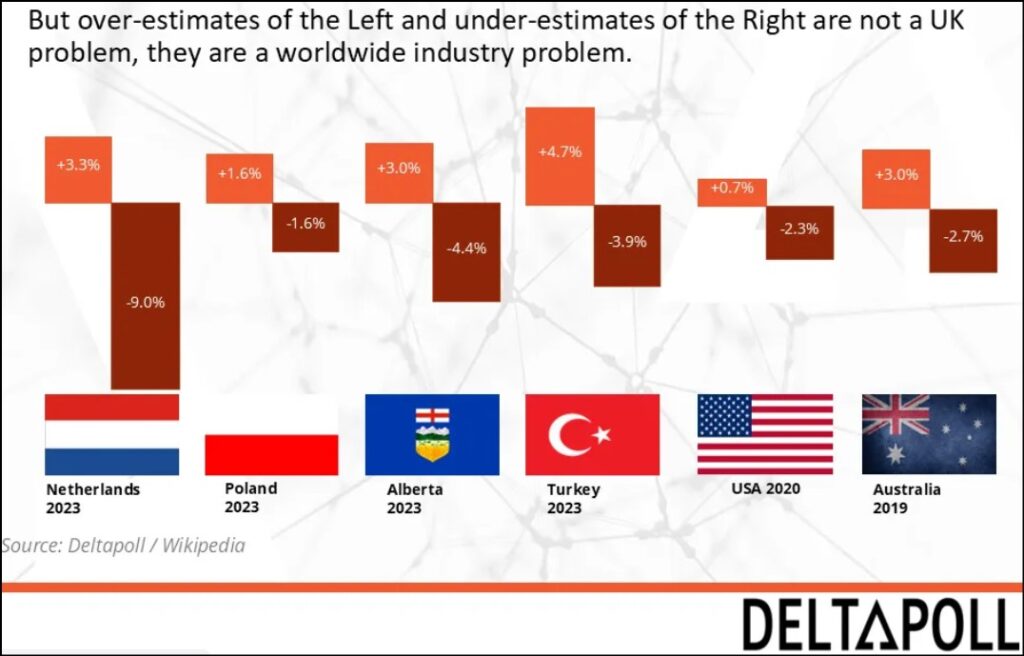

Over-estimating the Left and under-estimating the Right is not just a UK polling problem – it has cropped up as a fairly consistent (but not universal) pattern across many countries, as can be seen in the Deltapoll slide in this piece by Mark Pack.

The industry has tried to counteract this skew through various means of political weighting, such as using previous voting behaviour.

Electoral Calculus states there is indeed suggestive evidence of a ‘shy Tory’ effect in 2024, with people who refused to answer voting intention questions or who replied “don’t know” being more likely to be Tory voters. This is also consistent with the findings reported by BMG and by More in Common about ‘undecided’ voters who were then pressed.

YouGov suggests that its past vote weighting fell down in 2024 because at the previous election in 2019 the Brexit Party endorsed the Conservatives in many seats. The result was that its panels had too many 2019 Tories who actually preferred the Brexit Party and then voted Reform in 2024, and not enough firmly committed Conservatives. Their paper does not raise the issue of whether it is staunch Tories who are most likely to avoid voting intention opinion research, but it seems to me that this conclusion is compatible with their evidence.

Find Out Now (which only produced one unpublished poll during the 2024 campaign) argues against the ‘shy Tory’ hypothesis. But in my opinion their data only counters the hypothesis that online research panels under-represent Tories in general, as opposed to the hypothesis (advanced by Electoral Calculus) that Tories may be reasonably represented in panels but are disproportionately likely to refuse or reply “don’t know” when faced with a voting intention question in a survey.

More in Common also states that there is possible selection bias affecting online panels as the recruitment processes appeal to the ‘overly opinionated’.

Age

Age was very strongly associated with how people voted last July, with Tory support concentrated in the older section of the electorate.

The report from Verian (the polling company which came closest to the actual result on percentage vote shares) focuses entirely on the issue of age, and concludes that those companies whose samples contained a smaller proportion of over-65s (after weighting) tended to be less accurate. But its presentation adds that other biases would also have played a role.

Find Out Now raises a different possibility on age, that it failed to locate Conservatives who were younger and less politically engaged (a group that is hard for pollsters to reach).

Summary

At this stage we are left with the suggestion that perhaps four or five factors may have contributed together to the polling miss, and none explain it alone.

There can be a problem with this kind of analysis, dubbed the “Orient Express” approach by Electoral Calculus, where multiple possible causes are examined and all those which affect the error are deemed part of the solution. In other words, as in the Agatha Christie story, if everyone/everything is responsible for what happened, then eventually no one/nothing is actually held responsible, and nothing is done.

On the other hand, looking at the underlying fundamentals, it seems to me that predictive opinion polling is a difficult business given the level of precision required and the volatility of today’s voters. There are many sources of potential error (apart from normal sampling variation), arising from which people get contacted, whether they reply or tell the truth or change their minds later, how the electorate is modelled, and how the answers from different groups are weighted to aim at representativeness. And errors that arise are difficult to eliminate methodologically, as they depend on political circumstances which vary from one election to the next, and also on the communications technology for conducting research which is constantly evolving and in different ways for different social groups.

Inevitably therefore pollsters are bound to make some mistakes (and not all will make the same ones). When they are lucky, the errors may cancel themselves out, more or less, and nobody notices them. When the pollsters are unlucky, the errors largely or entirely mount up in the same direction.

Further, more thorough analysis will be possible once detailed data becomes available from the academic British Election Study and its extensive voter research.

The British Polling Council, to which all the main pollsters belong, is also planning to hold a public event to discuss these issues, probably in April.