ICO sets out new targets for improvement

John Edwards is clearly adapting to life in the UK, seven months after he arrived here from New Zealand to take up the role of Information Commissioner.

Launching his three-year strategic plan for the Information Commissioner’s Office yesterday, he succeeded in saying ‘day-ta’ most of the time, although he did manage to come out with at least one ‘dar-ta’.

While data protection (however pronounced) is certainly the main focus of his attention and indeed the dominant activity within his budget, the new Edwards plan is also important for those concerned about the FOI side of the ICO’s work.

To his credit Edwards has recognised publicly as well as privately that the substantial delays in the ICO’s handling of FOI complaints are not acceptable. In his speech he said that the administering of FOI law ‘requires fundamental change, and that change has to start in my office’.

He and his team have also shown a welcome willingness to engage with the FOI community and discuss (in his words) ‘how we fix a system that clearly needs fixing’.

As the ICO leadership itself recognises, things are now at the stage where requesters need to start seeing practical results rather than just hearing expressions of intention.

As part of its plan the ICO announced new objectives for its work on handling complaints under FOI law and the Environmental Information Regulations (EIR). These include:

• ensuring that less than 1% of its caseload is over 12 months old

• reaching a decision on 80% of complaints within six months

• ensuring that 66% of tribunal appeal decisions go in the ICO’s favour

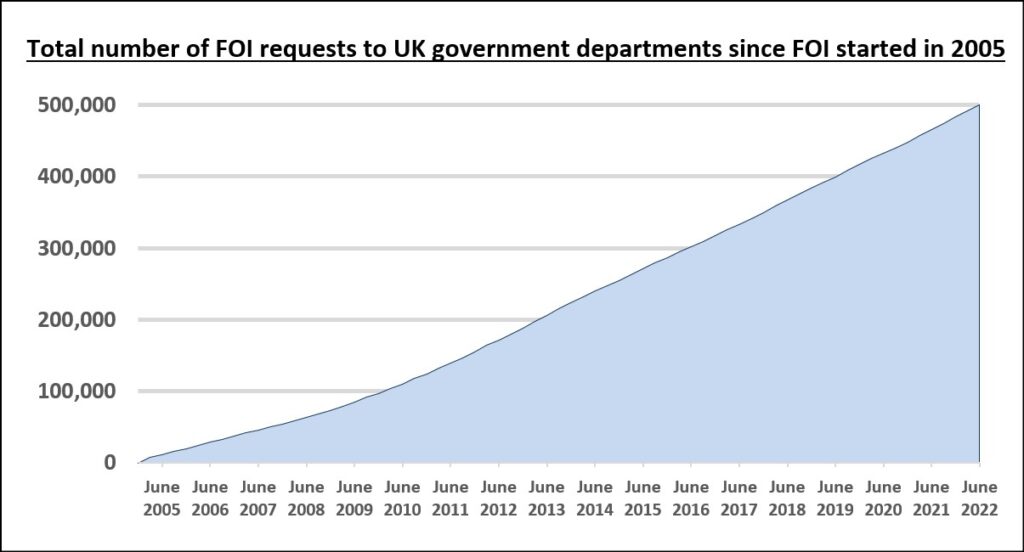

The current serious casework delays are illustrated by new up-to-date statistics which the ICO also released yesterday, with a commitment to do this regularly.

This is a valuable improvement, because in recent periods the ICO has only been publishing an inadequate series of datasets which are outdated, patchy and limited to closed cases.

The latest figures (for end of June 2022) show that 7.2% of active cases were over 12 months old. The ICO had reached a ‘first decision’ within six months on only 67.7% of cases.

The new dataset of open casework reveals that the ICO is still investigating one complaint relating to Brent Council nearly 26 months after it was made in May 2020.

There are 25 FOI/EIR cases that were still unresolved over 18 months after they were received. Of these, one of them actually involves a complaint about the ICO itself.

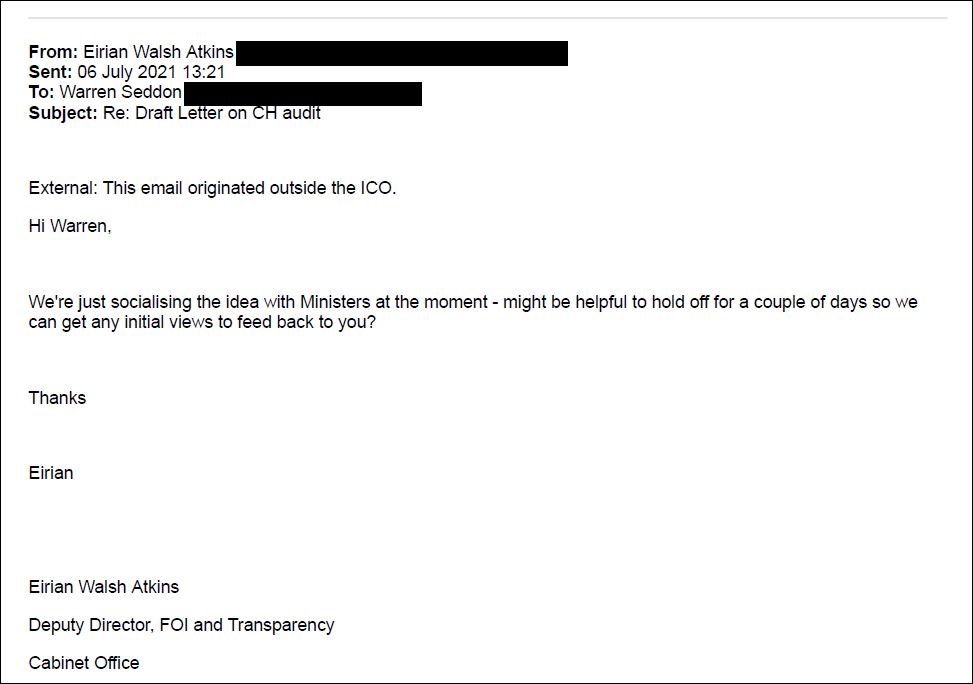

But the public authority which features by far the most frequently in these long-delayed cases is the Cabinet Office, which accounts for nearly half of them – 11 of the 25 involve complaints about its refusal to supply information requested. It is not clear whether this is because the Cabinet Office handles especially tricky issues or whether it is particularly slow and difficult about cooperating with ICO investigations, or indeed both.

As for the ICO’s performance objective for when its decisions are appealed by dissatisfied requesters or authorities, I have done a very quick analysis of tribunal cases so far this year, and the target of 66% appears pretty close to the current success rate. My rough calculation produced a figure of 68% (it is based on the summary outcome listed on the tribunals website without checking the details of individual cases).

ICO staff accept that some of their decision notices will inevitably get overturned, but there is always a risk that faster processing of cases can lead to more reversals later.

The ICO says its new approach will include more active prioritisation of significant cases and greater attempts at speedy resolution of disputes without the issuing of a formal decision notice.

For the ICO to improve its FOI casework handling is important and will be a relief to frustrated requesters.

However it is essential as well for the ICO to tackle the crucial systemic issues of poor performance on FOI by numerous public authorities. This week the ICO also released a new framework for regulatory action.

While it is understandable that ICO staff wanted to have this revised policy in place before implementing a tougher stance, it is unclear for the moment how much tenacity will be deployed in carrying out its series of measures and enforcing better standards.

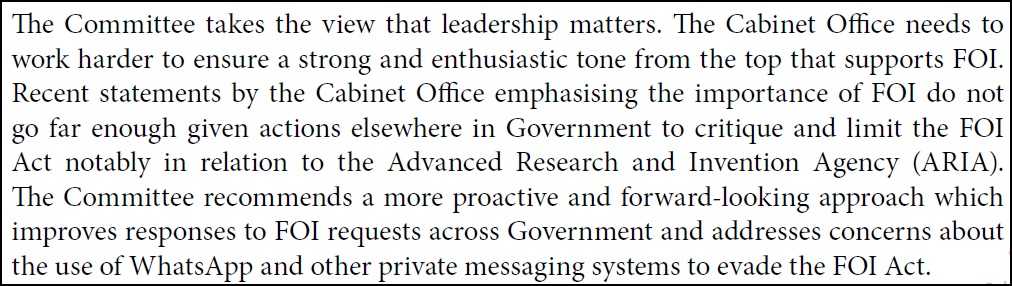

One early promising sign could be the practice recommendation it delivered this week to the Department of Health and Social Care, reprimanding the department over its failure to properly search non-corporate communication channels when responding to FOI requests.

In the Q&A session at the launch I raised one particularly egregious example of FOI deficiency, the fact that in the latest set of government statistics the Department for International Trade had breached the legal deadline for replying to requests an extraordinary 55% of the time.

I asked Edwards what more evidence he would need before taking enforcement action against a badly performing authority and he replied simply: ‘None’.

If this does indicate a much firmer attitude is being adopted, that then is good news and will be strongly welcomed by requesters pursuing their legal rights to information.

I understand the ICO has taken up the issue directly with the DIT. But how persistently determined it will actually be in tackling this sort of blatantly inadequate FOI record remains to be seen.

Edwards announced that he had persuaded government to set up a cross-Whitehall senior leadership group to drive improved compliance on data protection within the civil service. There is some hope within the ICO that this could in future be extended to cover systemic issues of government FOI compliance too.

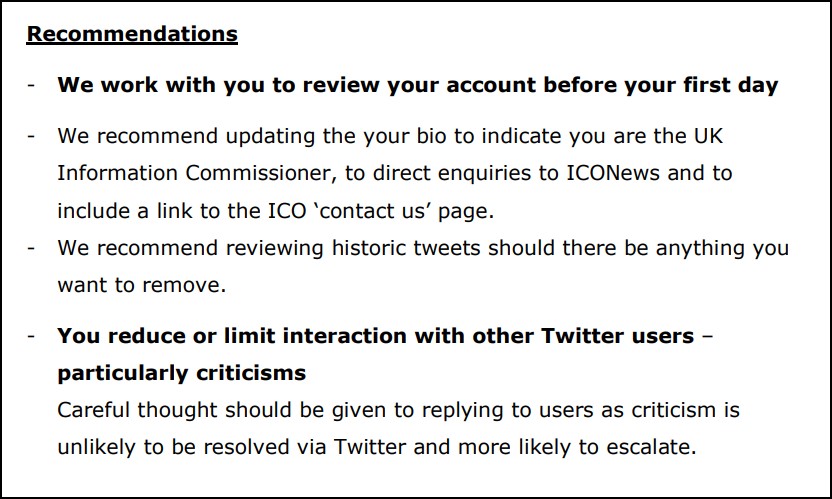

Unlike his predecessor Elizabeth Denham whose extent of contact with the Cabinet Office had become minimal by the end of her tenure, Edwards says he’s happy with the level of engagement he has been getting from the Cabinet Office.

Edwards also stated that the ICO will be publishing its internal staff training materials on both FOI and data protection, and this is expected to happen soon.

The ICO has initiated a consultation exercise on the three-year plan. If you want to express your views, you can do so here.

ICO sets out new targets for improvement Read More »