Twenty Years of FOI: A User’s Perspective (My presentation to the ICO)

An edited version of a presentation I gave last month for staff at the Information Commissioner’s Office about my perspective on FOI and the ICO. Many thanks to the ICO for asking me to address them.

Thank you very much for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to have this opportunity to share my thoughts on freedom of information from the user’s perspective.

That perspective goes back about 20 years or so, because I’ve been making FOI requests since the law came into force in 2005, primarily as a journalist. Before that I made requests under the previous system, the Code of Practice on Access to Government Information, a much weaker system than the FOI law we have today.

During my time at the BBC, I specialised in using FOI, both submitting requests myself and advising and training other journalists on how to use the law effectively. I left the BBC around four years ago, and since then I’ve written a practical guidebook for FOI requesters.

So over the past two decades I’ve seen a lot of FOI in practice, and when people ask me for an overall verdict on FOI – is it working well, or not? – I have sometimes described it as a ‘tale of two giraffes’.

Of the two giraffes photographed in this slide, one is in London Zoo, and the other is in Whipsnade Zoo in Central Bedfordshire. Three years ago I was doing some research into zoos, and I asked for the latest inspection reports on these two zoos, which should be a very simple FOI request.

Central Bedfordshire Council sent me the latest inspection report on Whipsnade within an hour. It was absolutely the way FOI should work.

Westminster Council, the council responsible for London Zoo in Regent’s Park, didn’t reply. After 20 working days. I sent them a chasing email. They didn’t reply to that. I had to complain to the ICO, and the ICO – thank you very much – did the usual thing of sending an email saying you must reply within 10 working days, and eventually five months after my request I got the report from Westminster.

So what one public authority had been able to do within less than an hour, it took another public authority over five months and the intervention of the regulator.

In other words, sometimes FOI works very well in practice, sometimes it works very badly. And obviously there’s also a lot of circumstances in between those two extremes. But the key point is that the experience of FOI as a requester is that it’s very varied. There’s both a positive side and a negative side.

The positive

Taking the positive side first, and looking back over the last 20 years, one of the very good things is the way that FOI has become well established as a tool that a lot of people use successfully.

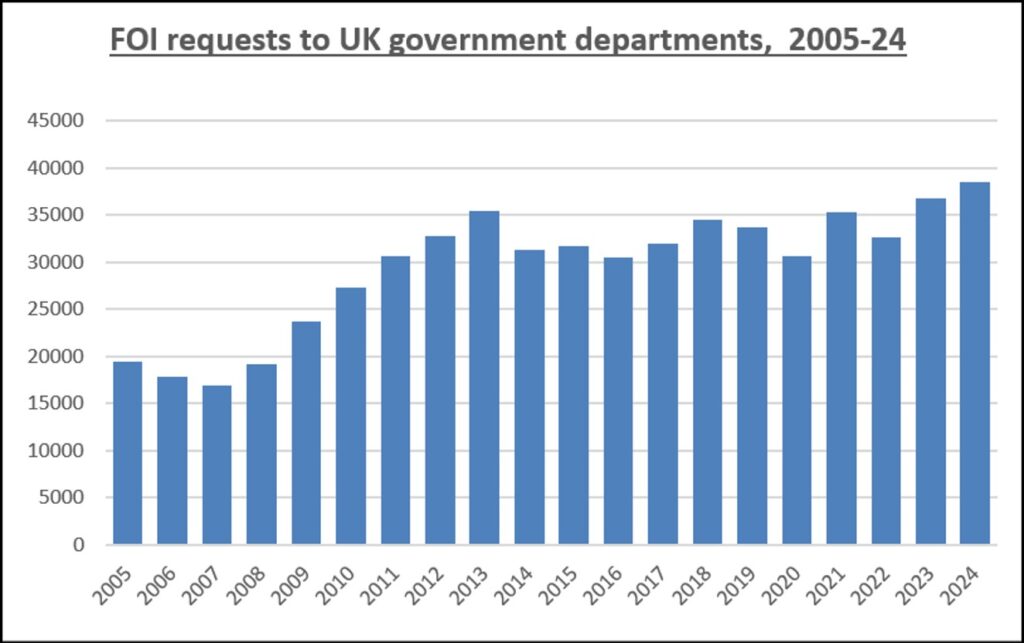

This is a chart which I’ve compiled from government statistics. I don’t think anybody else, by the way, is analysing these annual statistics in the same way that I do, keeping track of them over every year going back to 2005. This shows how in terms of central government departments, for the first few years the number of requests increased quite steadily until about 2013. Since then the numbers have been fairly steady over the past 10 to 12 years or so, maybe 35,000 FOI requests annually to government departments.

As you know we’ve only got statistics for central government bodies. So this is only a very small sample of FOI requests. Yet even so it’s one way of showing that FOI has become well established.

However, that fact obviously hasn’t gone down well with some people. For example, Tony Blair, who said that introducing FOI was like giving people a mallet to hit him over the head with, and that it was one of his two biggest mistakes. He famously wrote these words in his memoirs about the introduction of FOI by his own government: “Freedom of Information. Three harmless words … You idiot. You naïve, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop … I quake at the imbecility of it.”

He’s not the only prime minister who disliked FOI. David Cameron complained about it. Theresa May was more measured in her memoirs, but also had criticisms. And Liz Truss said in her memoirs: “Constant questions about who you’ve met and why … innocent meetings are privy to the press and often deliberately misconstrued.” She does, however, from her point of view, get the chance to blame Tony Blair for it.

What I think about these remarks is that actually they show in a way that FOI is working, at least in some cases. FOI should sometimes be uncomfortable to people who hold positions of power. That’s part of the point of it. If people in power were always very happy about the way that FOI worked, then it wouldn’t really be doing its job. So these quotes from former prime ministers don’t put me off FOI, to my mind they strengthen the case for it.

It’s really quite striking how FOI has reached the level of use and acceptance where it would be pretty politically impossible for a government to seek to weaken the law significantly.

We can see what happened when sometimes they have tried to take certain steps in that direction. For example, the Cameron government set up a review, a Commission on Freedom of Information, which included people like Jack Straw and Michael Howard, former politicians who were thought to be very sceptical about FOI. I think the government at the time was probably hoping that this review would report and pave the way for some restrictions on FOI to be introduced.

But actually when the review looked at how FOI was working in practice (and I’ve got to say full credit to people like Jack Straw, who I know from my own conversations with him had had doubts about FOI), it concluded that the law was generally working well, that it enhanced openness and transparency, and there was no evidence that it needed to be altered. It came down against the suggestion that was around some time ago of introducing charges for FOI requests. In fact, the review even said that in some cases the right of access should be increased.

FOI has become well established, it’s difficult to change in principle, and it works well in practice for many people.

So what is the point of FOI? It’s not to hit Tony Blair on the head with a mallet. As far as I’m concerned, primarily as a journalistic user, its purposes are to find out the truth, to hold power to account, to expose wrongdoing, and to give the public useful information.

There are journalists who’ve made a lot of use of FOI, and others who do so more occasionally, who are trying to achieve these kinds of aims. If we look at a recent list from a website that aggregates news stories, which I searched for freedom of information stories, the selection here is about London’s dirtiest streets, Thames Water (that must be an environmental information request), banks and fraud reports, stories about universities, others about councils, a wide range of themes.

When I was at the BBC we did go to some lengths at some times to collate together on the website a lot of FOI stories that had been done across the organisation, and again what this illustrates is the range of different issues covered, a lot of them very local – health stories, stories about a particular NHS trust, often very much of use to people in the local community, police stories, home affairs, politics stories about what councils are doing, transport stories. One could go on, but it shows the tremendous wealth of topics that FOI enables journalists to find information about in the public interest.

So to give some context about journalistic use of FOI, what do journalists get from FOI requests?

First of all, FOI might directly get the news story – the FOI disclosure in itself is the story, the headline.

But that’s not always the case. Sometimes for us FOI is a piece in a jigsaw, it’s an element in the story. That’s sometimes because you have a case study and FOI gives you overall statistics or context. Sometimes it’s the reverse, you might have some overall context already, but with the use of FOI you can get information about particular examples that help to fill out the story.

Sometimes FOI obtains background information. It doesn’t end up getting reported directly, but it points you in certain directions. It enables you to decide what you’re going to research, it informs questions to put to people in interviews, it helps with how to find out stuff from contacts, and so on.

And of course sometimes you get nothing useful whatsoever. All of us who’ve put in a number of FOI requests have sometimes found that the outcome was nothing of any use.

To give some examples of all of this, here is a story I did some time ago when I was at the BBC about Prince Charles, as he was then, urging Tony Blair to meet campaigners against genetically modified food. Charles doesn’t like GM food and he was lobbying Blair as prime minister about the issue. This fits into the example of the disclosure as the news story.

I have to say on this example that it took me two years to get this information out of the Cabinet Office, and it took four rulings from the ICO at different points in that process. I’m grateful to the ICO for that, but it also shows the kind of attitude sometimes of the Cabinet Office. For example, first of all neither confirming nor denying that they held the information, then trying to insist it was not environmental information, and so on.

To give a different kind of example, here’s a story where the BBC had some case studies about people who were scammed into paying money to get COVID vaccines. It was the kind of thing that a lot of scammers piled into, trying to get money out of people by sending them bogus messages. But is it a big problem? Well, FOI enabled the BBC to get some kind of national overall context and say there’s over a thousand reports, people have lost nearly £400,000 to scammers through this scam, so it is a significant thing. That’s an example where FOI is a piece in the jigsaw, you’ve got the case studies and then you’ve also got overall statistics.

Next is a different kind of example of a story I did once, and this is one of my favourite examples of the success of FOI, for reasons which I’ll explain.

This is about which makes and models of cars are most likely to fail MOT tests. When I first requested this data from a Department for Transport agency, I was told that this information would not be released to me under the commercial Interests exemption, presumably because it would be damaging to the commercial interests of people who sold cars that didn’t do well. Again, I appealed to the ICO, and the ICO again ruled in my favour, forcing the Department for Transport agency to release this information, which I regard very much as in the public interest, as useful to potential car purchasers, knowing which cars are most likely to do well in MOTs and which aren’t.

This information is now released annually routinely as open data. In other words, what for 18 months the Department for Transport told me was so confidential it could not be disclosed is now released routinely and proactively. It’s a very good example of the benefits of FOI, transforming information that was previously secret into something which is released as a matter of routine.

Another instance of this is food hygiene reports, where again we had councils refusing to release food hygiene reports, and where again the ICO stepped in and ruled that it’s in the public interest for the public to know which food outlets have good food hygiene and which don’t. And this has now become information which the Food Standards Agency releases routinely as a matter of course. We have ‘scores on the doors’, so you can see on the outside of a restaurant how it’s doing.

That transformation has enabled journalists to do this kind of story – how do restaurant chains compare? To give the quick summary, if you want to go to a place with good food hygiene consistently across the country, when we did this study Nando’s had a satisfactory score everywhere. So you can’t say you don’t get useful information out of this kind of talk.

Another example I want to share illustrates the kind of information I think of as practically useful. This was a graphic I generated based on data from individual hospitals, showing A&E waiting times by hour of day and day of week. Each line represents a different hospital. The pattern is clear: if you turn up at midnight, any day of the week, you’re likely to wait much longer than if you arrive around eight o’clock in the morning.

That’s useful information, and yet it wasn’t being published at that level of detail by NHS England, even though it was collecting the data. I had to request it through FOI. Without the law, I wouldn’t have been able to obtain it.

The negative

So that’s some of what I see as the positive potential of FOI, and what I and others have achieved with it, but on the other hand FOI doesn’t always work well. Journalists frequently complain about delays and obstruction. Here’s a headline from the Press Gazette, the news trade website: ‘Freedom of Information in the UK sinks to new low’. This story is from 2024, last year, but you could probably find a version of that story in the Press Gazette every year. Because FOI still all too often doesn’t function as it should.

I first want to make a general point. Part of the problem is a broader shift in official attitudes. In the past there were more people in positions of power, contrary to the views of Tony Blair, stressing the benefits of openness and transparency. In the early years after the law came into force in 2005, there was rhetorical support from government for openness. Lord Falconer, the minister responsible for FOI at the time, attacked the ‘culture of secrecy’ – you don’t hear government ministers now saying that kind of thing.

Then under the Cameron government, the Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude was very keen on open data – which is not the same as FOI, but is part of a wider transparency agenda.

Again we don’t hear that from ministers today, that rhetoric about the benefits of transparency and openness. And this climate does have an impact on how public authorities behave, and in some respects they are more resistant to releasing information.

Here’s an example. Early on in the FOI period I obtained documents showing how the Metropolitan Police Special Branch had monitored the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the UK over 25 years. They were released in 2005. There is absolutely no way the Metropolitan Police would release that information today. In the early years of FOI they were generally more committed to transparency, and it’s an example of how things have deteriorated.

Sometimes I’m accused of being too cynical, so let’s take a look at what the chief executive of the Environment Agency, Philip Duffy, said at a conference last year: “I see these letters and these FOI requests and I’ve got great volumes of them, and I see local officers going through contorted processes not to answer when they know the answer and it’s embarrassing.”

This is a clear statement from the chief executive of the Environment Agency about how his officials behave, trying to avoid releasing embarrassing information. This is obviously a completely unsatisfactory state of affairs. It’s not only the Environment Agency, in some ways what we have here is Philip Duffy being more honest about how FOI sometimes operates than other public authorities often are.

Another example: a slide from internal Cabinet Office training on FOI. It says: “If you don’t want to appear in tomorrow’s newspapers, consider carefully what you send out.” That’s basically telling people don’t release stuff which is embarrassing, and it’s not what the law says. There’s no FOI exemption in the Act for “Stuff you don’t want to appear in tomorrow’s newspapers”. That should be a totally irrelevant consideration, yet here we have it appearing in the Cabinet Office guidance to staff on how to handle FOI requests.

I do think journalists in particular often have a problem with how their FOI requests are handled. To give just one example of the sort of processes that come into play, the Financial Conduct Authority guidance to staff on FOI explicitly states that approval for journalists’ requests must be “obtained from press office”. It’s very far from being the only body where this is the case, very far indeed, and I see two problems with this. First of all, it inevitably increases delay, because the reply has to be checked by the press office. But secondly, for people who work in the press office, their job is to protect the reputation of the organisation where they’re working. That is entirely separate from FOI considerations and they should not be involved in approving the answers to FOI requests.

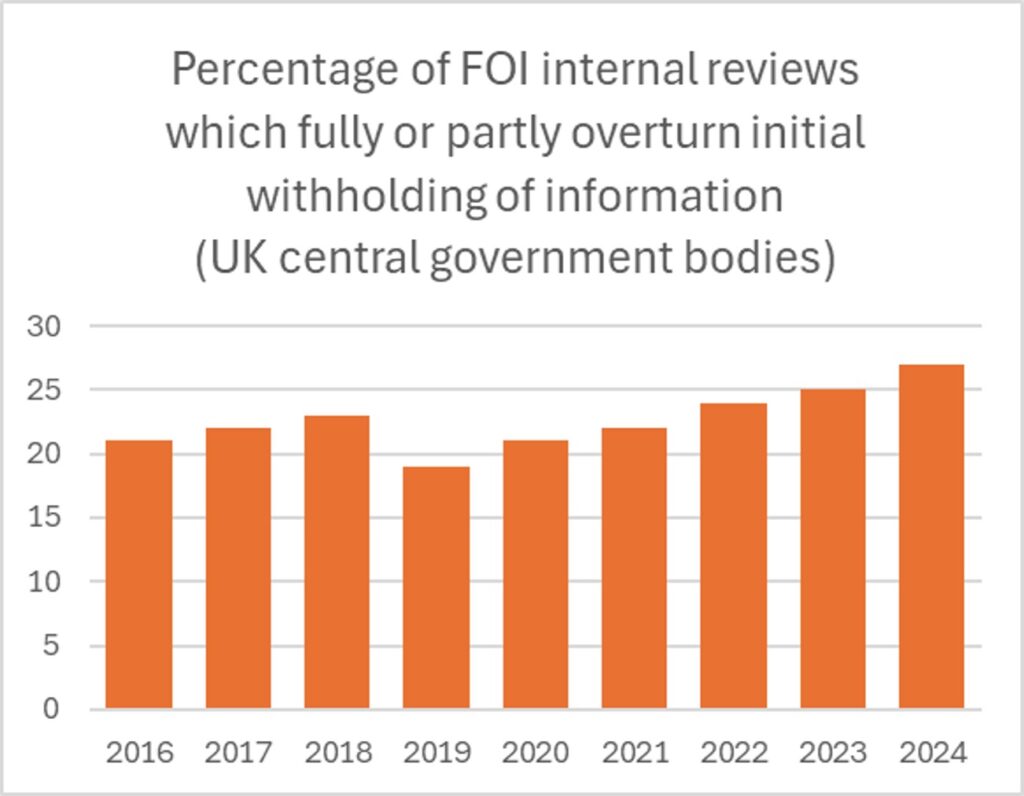

This is another statistical analysis I’ve done, of how often internal reviews change initial refusals. Again, as far as I’m aware, I’m the only person who is analysing the statistics issued about central government FOI requests to this extent. This chart shows how often internal reviews overturn, partly or entirely, an initial refusal from a government department that information should be withheld.

It’s only because we have statistics for central government that we can do this. We don’t know what the position is for all sorts of other public authorities. But what we can see here is that maybe 20 to 25 percent, and perhaps increasing, of internal reviews overturn an initial refusal, partly or entirely.

You can look at this in two ways. One is to say that internal reviews are actually doing their job, scrutinising the initial decision. But I also think that this rate is surprisingly high, suggesting that very often at the initial stage people are refusing FOI requests in ways that they should not be. This isn’t even the ICO getting involved. This is just somebody else in the same organisation saying you should have released it, and I think it points towards an initial level of obstruction in some cases.

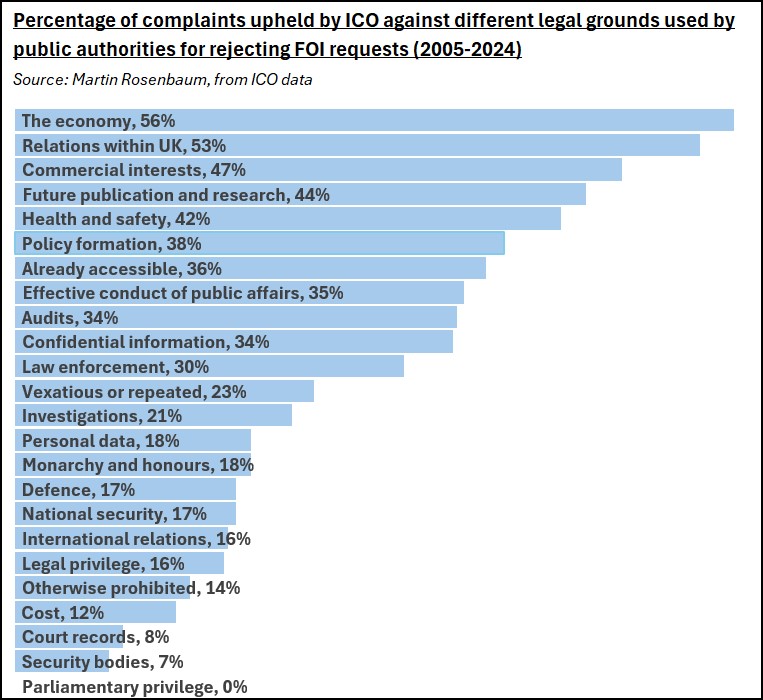

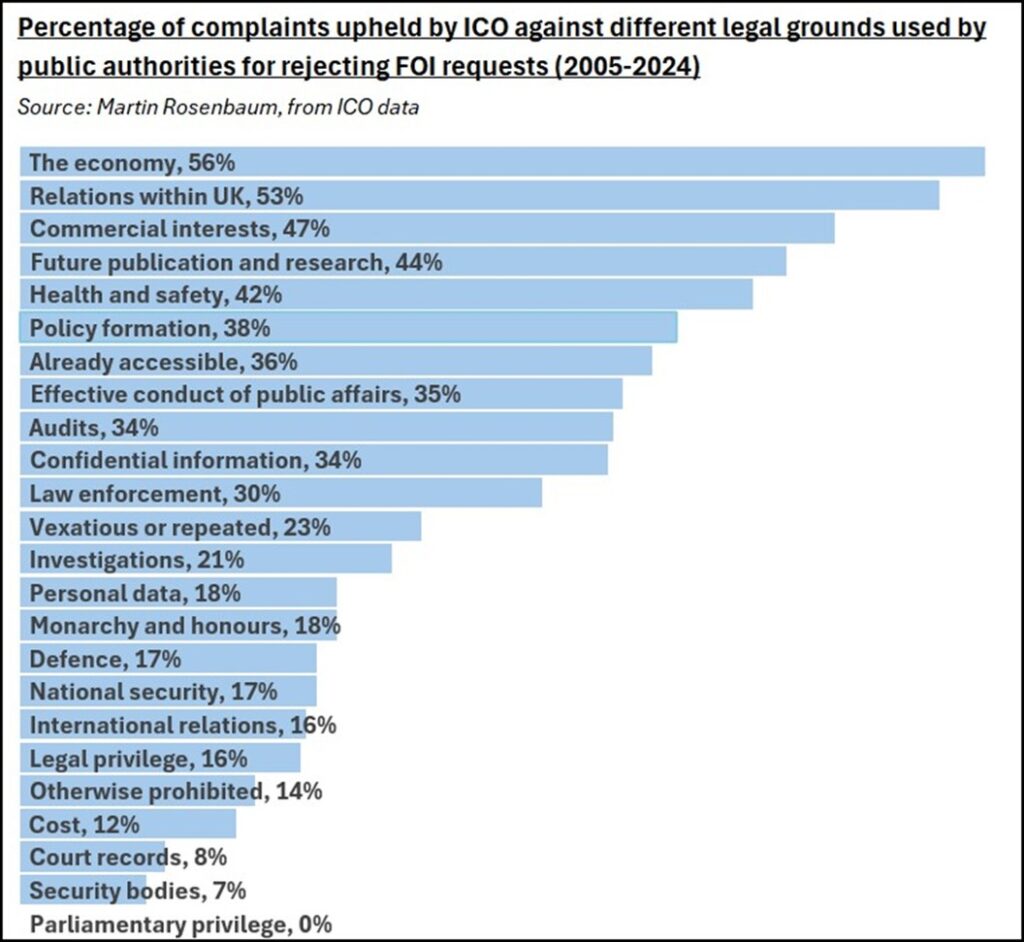

Now let’s look at how often the ICO overturns decisions made by public authorities. This is an analysis I did based on a dataset going back to 2005 which the ICO released last year. I don’t know to what extent this kind of analysis is done internally within the ICO or not.1

What I find really striking about this is how for some of these exemptions, the ICO overturns them so often. Taking the ones at the top, the economy and relations within the UK are not so often used, but commercial interests is a very frequent exemption used by public authorities to turn down requests. Yet of the cases that have been appealed to the ICO, basically in half of them the ICO has overturned it.

And there are other exemptions – future publication, policy formation and so on – where the ICO is very frequently overturning their use. What that really points to is a systemic issue that these exemptions are being overused by public authorities. And what the ICO in my view needs to do is draw attention to that and say there is a widespread problem of the overuse of certain exemptions.

I’m aware that the ICO has issues about resources and its level of casework. So if authorities could be stopped from overusing those exemptions, then that will be a way of reducing the level of casework that the ICO gets, and this is another reason why the ICO should be vocal in flagging the systematic overuse of certain exemptions.

The ICO

As I’m talking to the ICO, I should tell you my view of the ICO. This is what I wrote in my book: “Despite problems of resource constraints and significant delay (and the fact that I sometimes disagree with its decisions)” – we’ll come onto that later – “its existence is one of the strengths of the UK’s FOI system”.

When I’ve done training for journalists, this is one of the points that I make, that it’s a strength of the UK system to have an independent body which can overrule public authorities. That’s not the case in some other countries, and the ICO’s role is very valuable.

Let’s take some aspects of its FOI work in more detail. On delay, I very much welcome what the ICO has done over the past couple of years or so to speed up its consideration of complaints about FOI.

In contrast there was an extreme example back in 2009, when the ICO ruled in my favour on releasing the minutes of a Thatcher cabinet meeting about the Westland crisis, where it took the ICO four years to reach that decision. That’s ridiculous. It’s an extreme case, but when the ICO takes that sort of time, then public authorities have tremendous incentives to boot issues into the long grass, turning down requests for information on the basis that by the time the ICO rules, no one will care about it. A lot of progress has been made in speeding up the ICO’s procedures, and it’s vital that it doesn’t deteriorate again.

The fact that the ICO now prioritises certain FOI complaints with significant public interest is also a welcome and valuable step which enables the most important cases to be dealt with most quickly. Maybe the threshold for prioritisation is a bit too high and probably more cases should be prioritised, but in general it’s absolutely right to have done this.

I’m also very pleased by the way that the ICO is now taking serious regulatory action against recalcitrant public authorities. For example, the enforcement notices and practice recommendations served on numerous police forces recently and rightly, because the performance of the police in FOI terms has often been very bad, as has also been the case for various government departments, certain NHS bodies and so on.

It’s much more effective for the ICO to take this kind of regulatory action, issuing enforcement notices, than the kind of situation that we used to see beforehand.

Take this example that I wrote about the Cabinet Office. You would have this flow of decision notices from the ICO referring to Cabinet Office delays as being unacceptable, unhelpful, extreme, protracted, considerable, unsatisfactory, excessive, prolonged, severe. One decision notice after another would say this, but nothing ever changed by just issuing decision notices where it says in passing that delays are unacceptable.2

In contrast taking proper regulatory action and issuing enforcement notices is the best way to achieve change from the most recalcitrant public authorities, and I’m very glad to see that the ICO has been doing that.

However, I’m not going to say that everything about the ICO is completely marvellous. I’m pleased about reducing delays, I’m pleased about the prioritisation, I’m pleased about the enforcement action. But I do think there is an issue about the quality of certain ICO decisions, and there are decisions where the ICO does not really address properly the balance of the public interest.

This includes recent cases where I’ve been successful in appealing ICO decisions to the First-tier Tribunal.

One example involves the House of Lords Appointments Commission and the citations provided for some of Boris Johnson’s appointments to the Lords. In my opinion it’s overwhelmingly in the public interest that the public knows what are the official reasons given for why people are put in a legislative assembly. The tribunal agreed with me on that point3 that the citations should be public. So the House of Lords Appointments Commission was forced to reveal them.

I was disappointed, however, that I needed to appeal to the tribunal in order to achieve this. This is a case where the ICO should absolutely have said it’s in the public interest for this to be out in the open, and people could then assess for themselves the reasons that Boris Johnson gave as to why people should be members of the House of Lords with the right to decide on laws everyone else has to abide by.

That’s one example, and another occurred just last month when the First-tier Tribunal ruled that I should be given information in a Cabinet Office case where the ICO had ruled against me on a public interest test.

The tribunal said: “The tribunal shares the appellant’s view that there is a strong public interest in upholding standards of good decision-making, transparency and integrity in public administration … In the tribunal’s assessment, the withheld material is relatively benign and does not contain candid or controversial exchanges. The tribunal finds that the Cabinet Office’s concern over inhibiting future frank advice is overstated and not supported by the content of the material in question.”4

Here we have another example of the ICO in my view not taking a strong enough stance on where the balance of the public interest lies, and then the tribunal has to step in. That means extra work for me as the requester to appeal to the tribunal, but it’s also extra work for the ICO, which then ends up trying to defend an untenable position at the tribunal, costing a lot of time and money, as well as being against the public interest.

I know there are other cases where the ICO has taken a position which has annoyed the Cabinet Office. But I think it doesn’t do that often enough, and the ICO should be more prepared to stand up to the Cabinet Office on cases like these.

Finally, I wanted to make one other point, and this goes back to what I was saying earlier about the public debate about open government. I’d like to see the ICO now speaking out more about the broad advantages of transparency. We need to be hearing the voice of the ICO more often in public discussion.

To give one specific example, a government policy document issued last year states that it’s going to extend the FOI Act to private companies that hold public contracts, and that the government will take this forward “in due course”. So it’s publicly committed, but we’ve no idea when it will actually do this, or even if it will really happen. It’s not in the current legislation.

This is the kind of thing that in my view the ICO should be talking about now. It should be stepping into this discussion and saying this is an important and valuable change that is needed, because so many services are contracted out in the way that our public sector now operates.5

I’ve left time for questions. Thank you very much indeed.

——————————————————-

1 During the Q&A session afterwards I was told that the ICO does do this analysis itself.

2 On the day after I delivered this talk, the ICO announced it was issuing a practice recommendation against the Cabinet Office due to its FOI delays.

3 ICO staff are keen to point out that the tribunal did not agree with me on everything and upheld some other parts of their decision.

4 The material in question can now be found here, if you want to decide for yourself whether its release will damage free and frank discussion in the civil service in future.

5 In the Q&A I was reminded that the ICO has issued a report on this topic, but the point I made was that this was done back in 2019.

Twenty Years of FOI: A User’s Perspective (My presentation to the ICO) Read More »